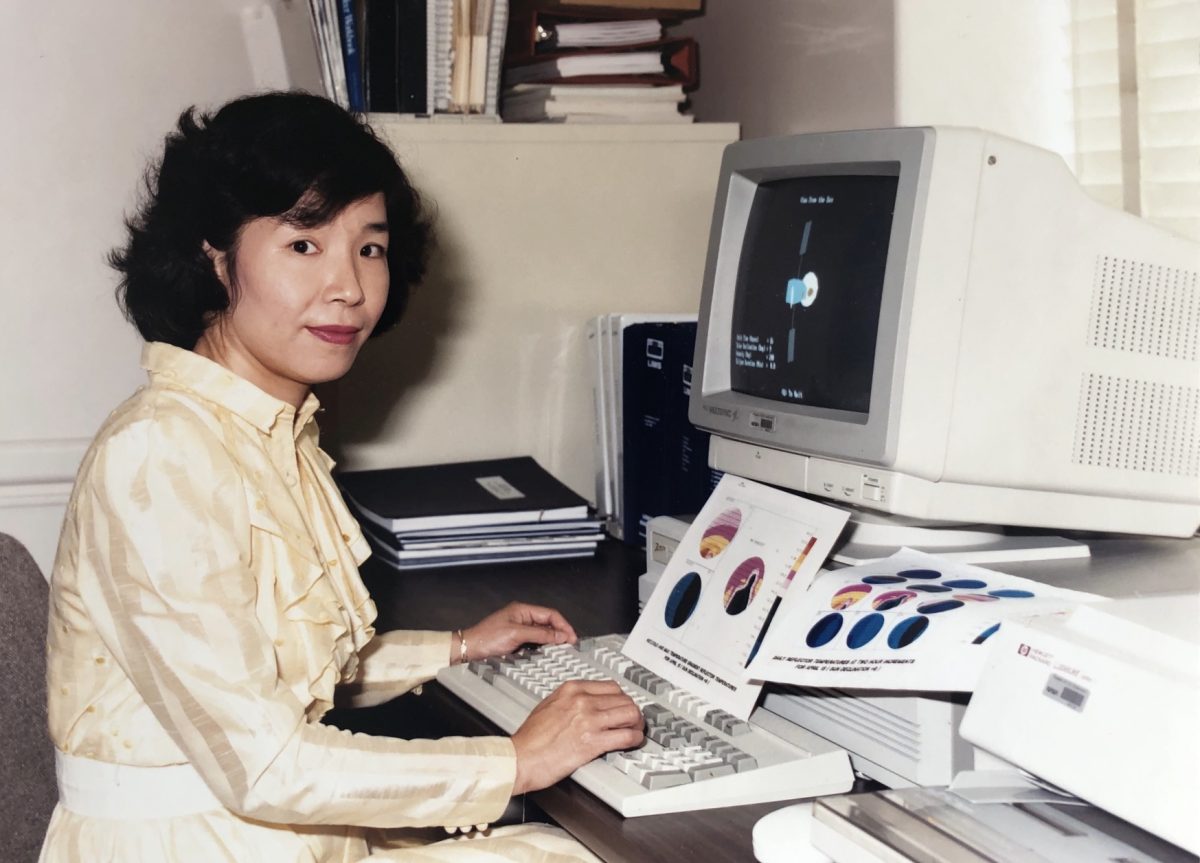

In 1983, Mei-Hwa Liao arrived at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio, to begin her work as a Supervisory Mechanical Engineer. It was the culmination of years of hard work, passion, and grit — and yet, it was also a familiar scenario. She was the only woman engineer in the entire Structural Mechanics Branch.

More than a decade earlier, in 1967, Liao had studied civil engineering in Taiwan at National Cheng-Kung University (NCKU) where she was the only woman in her department. Later, she moved to the United States to pursue a graduate degree in structural engineering at the University of Detroit. Again, she found herself the only woman student in her department.

“I was scared when I entered the department building,” Liao recalled. “All the boys were sitting in front of building…watching me walking.”

Liao recalled that at the time, during the late ‘60s, the engineering field was heavily male-dominated. As a result, she said people didn’t always “trust her ability.”

“Some friends, very close friends, even [would] say that I was hired as a vase for decoration only,” Liao said.

At NASA, she encountered similar doubts. Early in her career at Glenn, one of her colleagues submitted a report to their supervisor questioning the accuracy of her work while she was away for vacation. Liao believes that, at the time, few of her co-workers understood her capabilities. She said they underestimated her, and didn’t show her respect.

“And after I prove[d] over [and] over, they start[ed] to respect me better,” Liao said.

Aside from being the only female in her department, Liao also had to navigate cultural barriers. While her co-workers would sit together in the cafeteria and talk about American activities like football, Liao often felt she couldn’t relate as she had never watched football before in Taiwan.

To bridge the gap, she taught herself. Every time there was a professional football game, Liao started to watch and try to understand the rules and players so that she could join their lunchtime conversations.

“I put effort to fit in because of the culture difference,” she said. “And I [did] see that since I started to feel comfortable to join their conversation, I [felt] better for myself, and people start[ed] to treat me like [a part of the] team too.”

Even though it was rare for women to pursue engineering during her childhood, Liao was not the first woman in her family to enter a technical field. For Liao, watching her older sister succeed in chemistry encouraged her to study engineering.

“My field was civil engineering. That’s a male’s job, but I [thought] because of my science background, I [felt] that I can handle it, and my sister in college was doing so well,” Liao said.

By 1995,12 years after she joined NASA, Liao was promoted to Chief of the Structural Mechanics Branch — the very branch where she had once been the only woman, and where she had to prove herself repeatedly. But as she approached leadership, she began to experience a shift in how she was treated. Colleagues had went from treating her with friendliness to with hostility.

“You can tell they are so hostile and not willing to give you information,” Liao said.

Despite these challenges, the work itself continued to bring her pride. One of the most meaningful projects she and her team worked on was the International Space Station.

“So we were so proud that the International Space Station was part of my team’s contribution. And it’s one project, you know, I was very proud,” Liao said.

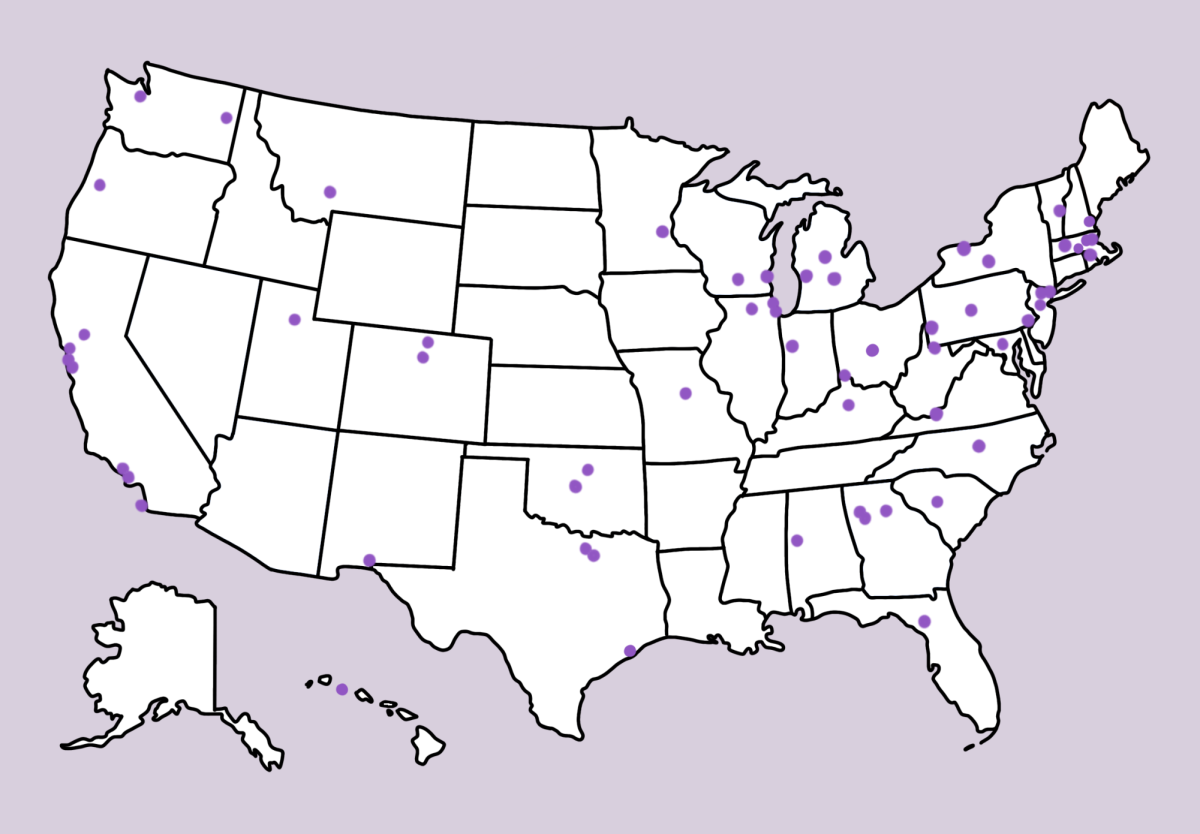

Liao retired from NASA in 2016 after 33 years of service. When she first joined, she had been the only woman in the branch. By the time she left, five of the 20 engineers in her department were women — a change she helped bring about.

“I was hired in 1983 you know, I was the only woman. And gradually, women came in,” Liao said. “Especially after [I became] the branch chief. I hired, other women, several women. So when I retired, the whole branch, a size of 20 people we [had] five female engineers.”