Since January, three California state universities have cut sports from their respective athletic programs, with one university eliminating its entire athletic department.

Collegiate sports programs — especially non-revenue sports — are getting cut due to tighter budgets, declining enrollment, and statewide funding cuts. Sports that don’t generate significant revenue for a university’s athletic department, typically any sport other than football or basketball, are considered non-revenue sports.

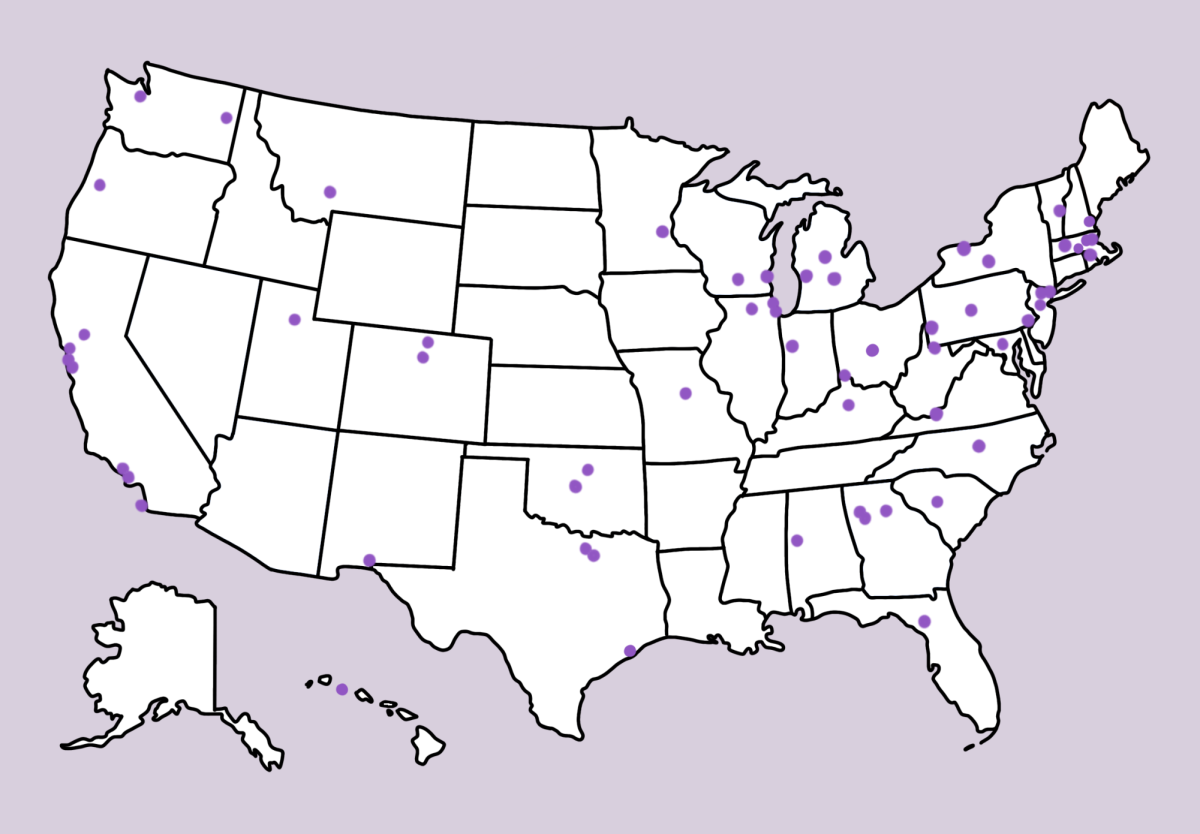

Some of these cuts are happening at nearby universities: California Polytechnic State University has cut its National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I swimming and diving teams; San Francisco State University has eliminated three of its Division II teams; and Sonoma State University has eliminated its entire 11-sport Division II program.

For junior Joshua Lim, hearing about these cuts brought up concerns and fear about the abrupt changes in collegiate sports programs, especially as a student in the midst of the soccer recruitment process.

“It’s kind of concerning knowing that things could change in an instant…all of a sudden [you’re] being told that you’re not going to be playing college sports the next year,” Lim said. “You commit so much to play at this high level…and knowing that there’s this possibility that you might not be playing the next year.”

Senior Giana Johnson has committed to playing softball at the College of San Mateo in the fall. While the cuts won’t significantly affect her, she knows student-athletes who are now without a school to play at.

“My best friend goes to Sonoma State, and she’s on the track and field team, and she has to figure out where she’s going to go elsewhere for college because she only went there for the track team…she worked so hard to already get [there]… that’s really harmful for student-athletes,” Johnson said.

With cuts to athletic programs, there are fewer roster spots available on collegiate teams for athletes to commit to. For Lim, the decreased roster spots make it harder for prospective athletes to be recruited, as only a limited number can play at a time.

“You don’t make the roster, you don’t play the game,” Lim said. “There’s only 11 people on the field. You always have to fight for playing time, and also just having that roster spot and being recruited. So I think this news is that they might decrease roster spots, and it will definitely impact my decision, and I’m sure it’ll impact many others.”

Additionally, as a result of the NCAA vs. House settlement, an agreement to pay student-athletes based on their name, image, and likeness (NIL), Division I schools will face significant financial impacts. Therefore, some schools have begun to allot more money to their revenue sports programs as they await their non-revenue sports programs’ elimination.

“I do understand that it might be harder to keep [non-revenue sports] because they don’t bring in a lot of money, but I do think it’s unfair how the other sports [gain] more privilege because they’re popular,” sophomore varsity swimmer Alexa Chang said.

Freshman varsity volleyball and track athlete Elaina Newman expressed the danger of making general assumptions about the popularity of certain sports.

“I think it’s definitely a bit extreme to assume people’s viewpoints so much on specific sports that they’re cutting the less popular ones and just keeping and even probably upping revenue a little bit on the more mainstream sports,” Newman said.

While the future of non-revenue sports remains uncertain, sports are a significant part of students’ lives — especially for athletes who plan to play sports to get into college.

“Only 7% of students in high school go to college for sports, and for those who have gotten into college, it’s a huge accomplishment,” Johnson said. “… For a lot of student-athletes, their sport is their entire life.”