Behind the Hong Kong protests

Hong Kong residents take to the streets one June 16 2019, protesting the extradition bill and calling for the resignation of Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam.

December 16, 2019

Millions of people across the world have come out to protest following controversies over the Hong Kong extradition bill, formally known as the Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation Bill 2019.

The history behind the protests today find their roots over 170 years ago during the First Opium War, when in 1841 the British Empire acquired Hong Kong from the Qing dynasty. The First Opium War was a reaction of the British Government when the Qing dynasty attempted to ban the importation of opium to China from Britain. Located in some of the busiest waterways of the China Sea, Hong Kong became an important trading city under British rule. Britain continued its rule of Hong Kong into the 20th century, obtaining a 99-year lease of the city in 1898.

After over 150 years of British rule, the transition of Hong Kong back to Chinese rule seemed smooth enough. Hong Kong was reunited with China under “one country two systems,” a principle describing the governance of Hong Kong as well as Macau, in which Hong Kong resides as a special administrative region while still part of China. This system is written into Hong Kong’s constitution, which defines Hong Kong as an inalienable part of China and yet prevents the Chinese government from practising its socialist systems and policies. Despite the transition’s initial success, protests and political dissent emerged over time, reaching its peak so far this year. The recent wave of protests had been set off by the Hong Kong extradition bill made in March of 2019.

The Hong Kong extradition bill, formally known as the Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation Bill 2019, initially sparked the protests. The bill declares that police forces from mainland China, Taiwan and Macau can extradite criminals from Hong Kong who have broken laws in their own jurisdiction. The bill was made in reaction to a Hong Kong resident who murdered his pregnant girlfriend in Taiwan, then returned to Hong Kong in 2018. Despite admitting to police that he committed the murder, authorities were unable to charge him for murder or extradite him to Taiwan due to past extradition policies. While the bill’s intention was to prevent Hong Kong from being a safe haven for criminals from mainland China, Macau and Taiwan, it sparked controversy among Hong Kong residents who feared that the Chinese government would be able to arrest Hong Kong residents at will, infringing on their civil liberties.

In response, millions of people took to the streets to protests not only in Hong Kong, but in cities across the world. After months of protests, the extradition bill was formally removed in late October. However, for many, the damage had already been done. The controversy the last straw for many Hong Kongers, and had already ignited the general anti-Chinese sentiment.

While it may seem like the extradition bill is a large part of the protests among many Hong Kongers, it is merely a trigger that set it off. The anti-Chinese sentiment held by many Hong Kongers can be better explained by the lack of change from the pro Chinese government, who can be held responsible for Hong Kong’s wealth gaps and expensive housing. Hong Kong has one of the least affordable housing markets in the world, with small apartments under 40 square meters averaging around 17,000 HK$ ($2,178) per square feet according to the Hong Kong Rating and Valuation department’s Dec. review, nearly double the cost in Burlingame, which is $1,126. In addition, Hong Kong’s median monthly household income in 2019 is 28,500 HK$ ($3,650) according to Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department compared to Burlingame’s median monthly household income of $9,900 according to the Census Bureau. The high cost of living combined with the inadequate median income level means that the standard of living in Hong Kong is drastically reduced, with the average living area per capita around 160 square feet, and reaching as low as 48 square feet per capita, only slightly larger than the size of a standard ping pong table. All the while the pro Chinese government of Hong Kong has failed to address these problems. To add insult to injury, the government is not completely democratic, with many leaders required to be approved by the Chinese government after an initial selection carried out by Hong Kong representatives, fact that had sparked the umbrella protests years earlier in 2014.

The protests that have stemmed from responses to the extradition bill and neglect of the pro Chinese government has developed into a movement with five demands: the classification of the protests not as a riot, the release of all prisoners arrested for the protests, an inquiry on police brutality during the protests, the resignation of Hong Kong’s Chief executive Carrie Lam and universal suffrage for the legislative council and chief executive, and the removal of the extradition bill, which had already been done. The protests were also decentralized and leaderless unlike past movements.

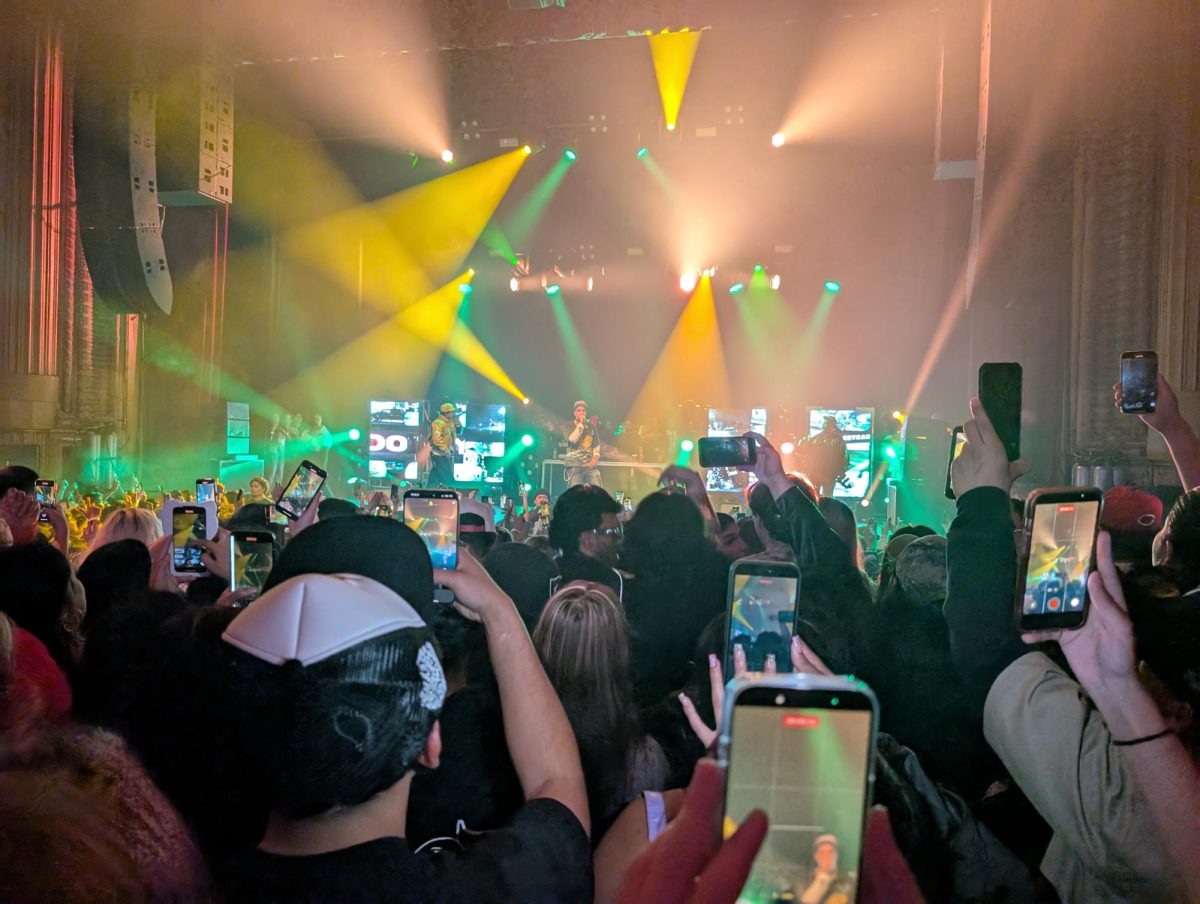

In seeking out these demands, demonstrations had been held with millions in attendance, not only in Hong Kong but all across the world. The SF Stand with Hong Kong Rally was held on Sept. 29.

“We had a gathering of 200-300 people all Hong Kongers and we also saw Taiwanese and Tibeten people,” senior Wesley Chou said. “The main thing that we were doing there was to raise awareness to the world about the situation in Hong Kong right now.”

With support from countries abroad, protesters can often be seen with American and British flags, as well as occasionally Donald Trump masks.

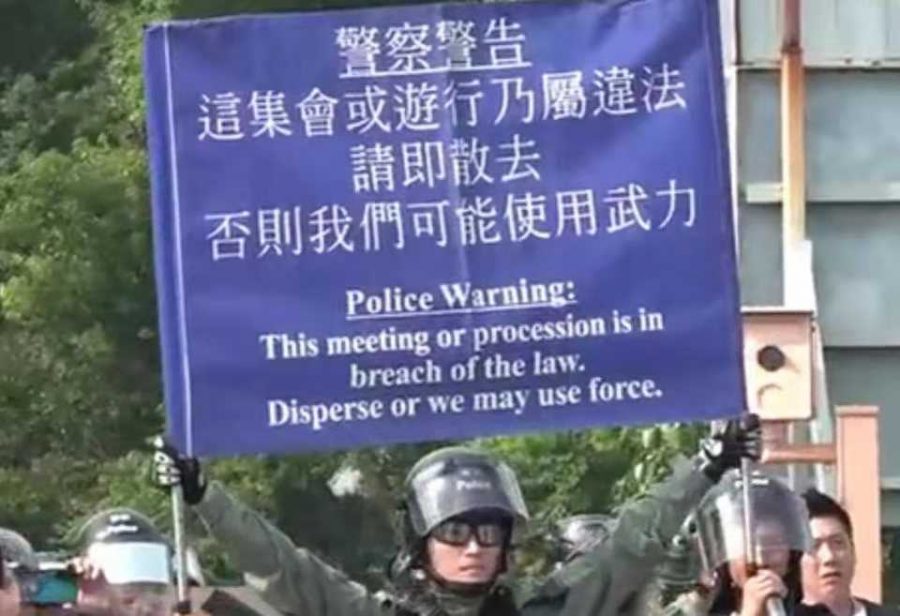

Protests have been continuing for over six months now, with violence on both the protesters and police side increasing. As recent as November, protesters occupied Hong Kong Polytechnic University, clashing violently with police who besieged the campus. Police forces would use tear gas and water, while protesters would hurl bricks and petrol bombs. In an exchange during the siege, a police officer was shot with an arrow. Demonstrations such as these shut down schools for days and weeks, and increased tensions.

As a completely decentralized movement, the recent Hong Kong protests can also be dangerous, with no clear leader to guide protesters in effective demonstrations or to negotiate with the Hong Kong government. As a result, there have been intense cases of violence such as in Oct., when a mainland Chinese banker was punched and attacked by a protester after giving a speech. Without a leader, protesters have had to organize over the internet, which has allowed individual anonymous protesters to have their voice heard online. Protesters have also used apps to their advantage, such as the police tracking app HKMap.live, which had been used to target and ambush police forces before it was removed from the Apple app store. The removal off the app also sparked outrage since it could also be used to prevent police brutality.

So why haven’t the protests ended yet? It is not in the best interest of China to grant Hong Kong all of the 5 demands. Granting universal suffrage for Hong Kongers could mean that the elected Hong Kong government would be anti-China and resist the integration of Hong Kong into China. Seeking complete independence from China would be a violation of Hong Kong’s constitution, and steps in that direction would ultimately be counterproductive for both Hong Kong and China. Interestingly, under British colonial rule Hong Kongers had even less representation in the government, with officials directly appointed by the British without an initial selection process, but caused little to no outrage compared to today.