Burlingame’s racist housing covenants

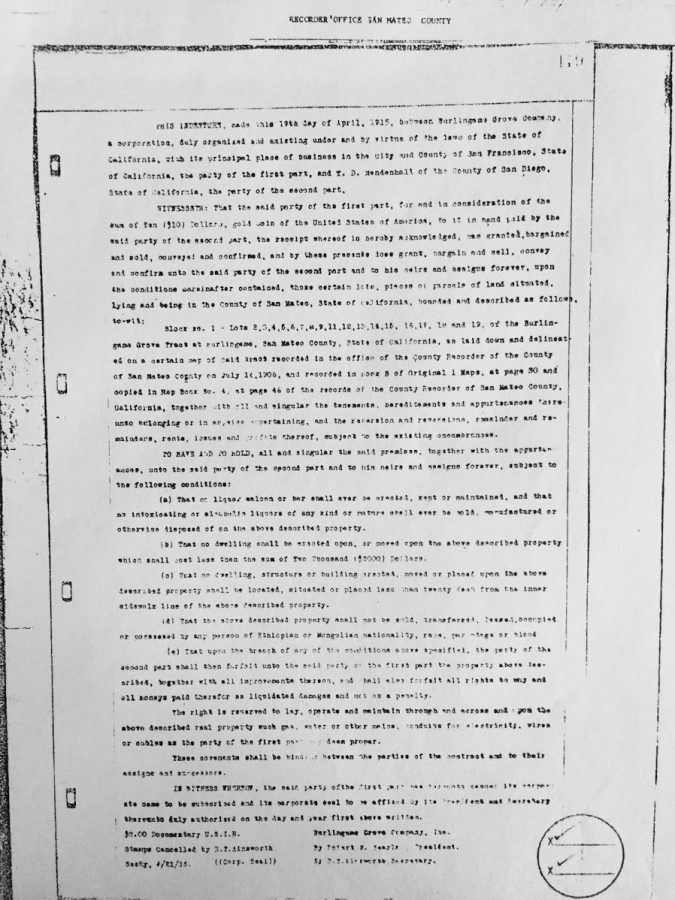

The covenant attached to one house on Mills Avenue that discriminates against Ethopians and Mongolians.

September 9, 2020

In May of 1932, a Chinese American family, the Lees, purchased a home in Burlingame’s Lyon Hoag neighborhood. The Lees were hoping that they could go unnoticed, but unfortunately, Judge Rockwell Stone lived in the same neighborhood, and he was adamant about keeping his neighborhood white.

“When we first moved into that house at the foot at Burlingame Ave., he circulated a petition to get these Chinamen out of here,” a member of the Lee family said in a 1993 Burlingame Historical Society Meeting. (courtesy of the Burlingame Historical Society).

However, the neighbors opted to forgo the petition and allow the Lee family to stay. Although the Lee family was able to reside in Burlingame, they had to overcome Stone’s efforts to segregate in order to do so. The Lee family’s story was also unique in the fact that their house did not have an attached covenant.

Covenants were popularized in the 1920s and ’30s after The Supreme Court ruled city segregation illegal in 1917 in the case of Buchanan v. Warley. Property owners and developers would create binding agreements as a loophole in which the selling, leasing, or occupancy of homes by people of certain races was prohibited. These proved to be very popular around the Bay Area, so that suburbs were able to be segregated legally.

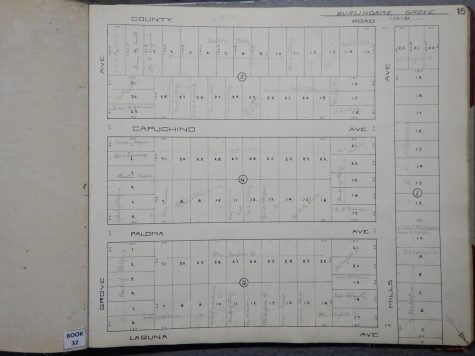

In one contract dated April 19, 1916, homeowners in Burlingame Grove agreed to discrimination against people of Asian and Black descent. Eighteen lots stretching the street of Mills Avenue were included in the contract.

“The above described property shall not be sold, transferred, leased, occupied, or possessed by any person of Ethiopian or Mongolian nationality, race, percentage or blood,” read the covenant.

Breaking such agreements would have led to eviction and forced liquidation as a retribution.

In the 1948 case of Shelley v. Kraemer, racially restrictive housing covenants were deemed void. Yet these contracts still remain attached to Burlingame houses today, and there is no enforceable way to demolish all covenants. This is because the covenants were written through private property holders with the purpose of bypassing anti-discrimination laws, meaning that the government cannot enforce abolition.

“So it’s really up to the folks that have these contracts to either rerecord them or revise those deeds in a way that can get rid of that language,” Mayor Emily Beach said.

In order to move forward from the racism built into Burlingame’s neighborhoods, citizens may take this opportunity to educate themselves on the city’s history. The City of Burlingame is also working in light of the recent civil rights movement to raise awareness amongst our community. They are planning to bring back “Burlingame United Against Hate,” a program that was first initiated after Burlingame High School was vandalized with hateful graffiti in September of 2019.

As the conversation of racism becomes increasingly more common throughout America, it is essential to recognize its influence in society. Burlingame made clear efforts to segregate through housing covenants in the early 1900s, and they continue to subsist over 100 years later.

View a transcription of the covenant here:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1Lm8DAepLvI6XKztsANbFS9Dp1zFjNusLjcflC6ns-8U/export?format=pdf