Looking back on how schools handled the Spanish Flu Pandemic

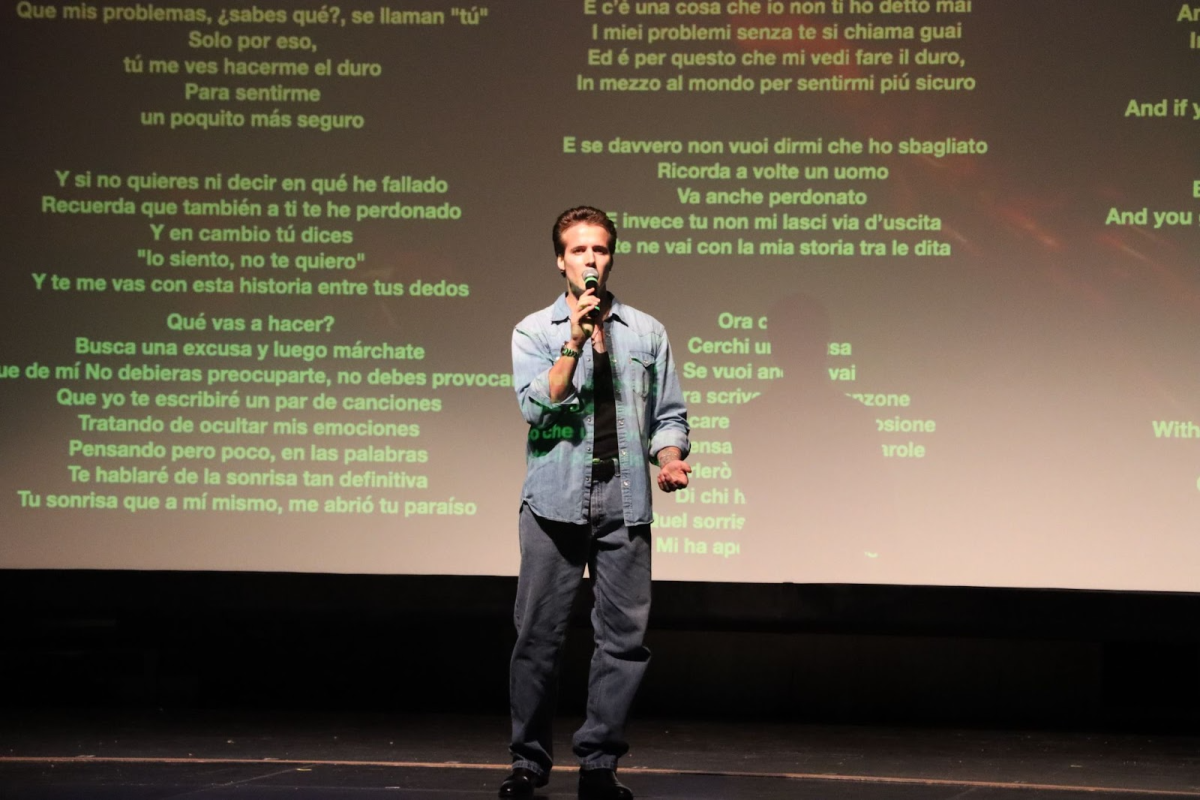

Photo courtesy of the San Mateo Historical Archives

Burlingame’s historic Howard Avenue School in 1915, captured by A.G.C Hahn.

November 24, 2020

Since the COVID-19 lockdown began in March, students have had to adjust to online learning. Luckily, with the availability of the internet, there are many resources and programs that allow students to learn from their homes. However, during the Spanish flu pandemic, from 1918 to 1919, students did not have access to similar technology options. Over a century ago, while schools across the country decided whether or not to close, influenza spread quickly throughout the world, killing an estimated 50 million people as World War I reached a climax. Students today can look back and appreciate the internet which allows them to learn from home.

Cases of influenza have been recorded since the 1830s and outbreaks have happened at various points in time all over the world. The virus was relatively known and researched before the Spanish Flu pandemic began, which is why many people underestimated and shrugged it off at first.

“When [this particular strain of influenza] came along, they really felt that this was just another flu epidemic,” President of the San Mateo Historical Society, Mitch Postel, said. “But it was so much more violent and deadly than anything that they had experienced in the past that it took not the United States by surprise, but the whole world.”

Influenza, like COVID-19, doesn’t have a high death rate among children and young adults. This meant that keeping schools open wasn’t impossible. Ironically, due to high poverty rates and unclean living conditions, schools were often safer than children’s homes, and schools wanted to keep children away from the dirty streets and potentially infected adults.

“Some cities, such as Boston and New York City, established school corps, comprised of medical inspectors who made daily rounds through the public schools to determine the health status of individual children and entire classrooms,” the public health reports from the National Library of Medicine wrote.

The government issued nurses and doctors to monitor students’ health in schools that remained open. Children were expected to wear surgical masks and stay distanced during free time; symptomatic students were sent home or to a hospital.

During the 1918 flu pandemic, the decision to close was up to the schools and closures were not implemented on a state-wide level, meaning that many schools in rural areas closed for weeks or months at a time with no contact. Some schools, like those in Redwood City and San Mateo, would open and close frequently depending on the number of cases in the area.

“They would have probably been better off if there would have been some edict from the state of California to help them get through that, but they didn’t have the same kind of governmental infrastructure that we have today and the schools were far more independent,” Postel said.

Similar to what the United States saw a few months ago, masking protests popped up around the nation, most notably in San Francisco near the end of WWI when many people ignored protective protocols; since there was more coverage of the end of the war, the protests didn’t get much attention. Many people didn’t take the pandemic seriously and case numbers spiked nearly every month.

“In October, it was really bad, and people took it seriously, and they wore their masks and they closed schools . . . but by November, people thought that it passed and it was just an influenza epidemic like we’ve had before. This one might have been a little sharper, but it’s gone. So, we get back to normal. And that was a big mistake … if they would have been a little bit more diligent right through it, then there could have been a lot less suffering,” Postel said.

By February of 1919, schools reopened permanently, but there was a lot of time to make up for.

“In San Mateo and Burlingame … without getting anymore pay, [teachers] volunteered their time to increase school days so that they could catch their kids up,” Postel said. “The teachers made sure that the kids didn’t suffer.”

Now, students can stay up to date on their work without putting their lives in danger during this pandemic via the internet, which allows teachers and students to continue curriculums without spending countless hours making up work when they return to in-person school.