Peninsula High School: navigating inequity

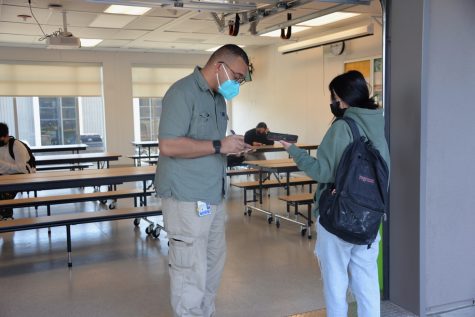

Leaver chats with Matthew Gallegos, a social science teacher at Peninsula. Both Leaver and Sacdalan spoke to the support and kindness of staff.

February 24, 2022

My conversation with Peninsula High School guidance counselor Elaine Llaguno and wellness counselor Lara Montoya took place in a counselor’s office at Burlingame. Even though the room is surrounded by the bustle of students entering and exiting the school, the office was perfectly quiet: thick walls blocked out the surrounding noise.

If our conversation was in Llaguno’s office at Peninsula, the students in the bathrooms above her, behind her and next to her would hear every word, she said. The walls are that thin.

“She’ll be like, ‘go to class!’ And they’re like, ‘sorry Mrs. Montoya, we’re going, we’re going!’ Montoya said. “As you can see, we really have to come with laughter and lightness because the work that we do and what our students come with is a lot. So we really pride ourselves on trying to lighten that weight.”

But the small slights make creating a carefree environment a heavy task for Montoya. One Tuesday, she asked the district office to send the measurements for a door at Peninsula that she wanted to paint.

“Even that, just getting the measurements — ‘well, can we hold off?’ and blah, blah, blah,” Montoya said. “What’s the big deal with getting measurements?”

Montya wants, more than anything, to brighten and improve the campus for students.

“What you see sets the tone for the rest of your day. If you’re already feeling a certain way, and it looks like a jail, it’s just that much more,” Montoya said. “The thing that can be done immediately, now, and doesn’t take a lot, is just painting the outside!”

Montoya and Llaguno both emphasized that a warm and welcoming school also requires the resources to host fun events on campus. Because Peninsula doesn’t have parent groups, foundations or fundraising opportunities like the comprehensive schools, the community is reliant on district funding.

Senior Natalie Leaver, who is part of the student leadership at Peninsula, told me that “just a little funding could do a lot — a lot — and go a long way. We can add so much more to this school if we just had the money.”

“I feel kind of helpless. Am I actually really in leadership?” Leaver said.

Painting the building or receiving the funding to hold events and activities wouldn’t just make the school more aesthetically pleasing — it would change the mentality of the students who attend Peninsula.

As Montoya put it, when students see the Peninsula campus, they assume that they are in trouble and undeserving of the “bells and whistles” that come with a “pretty” comprehensive campus.

Meanwhile, the staff is packed into a teachers’ lounge that is just 245 square feet. An English Language Development coordinator currently works out of that break room, English teacher Caroline Wisecarver said. And yet, teachers and staff are still calling for more faculty at the school, citing the additional support that each student requires at Peninsula.

Wisecarver counted four roles that every teacher at Peninsula plays. First, they are teachers — and some bounce between subjects. Wisecarver, herself, began at Peninsula as a physical education teacher. Second, they are often department heads. Although Peninsula is a small school, each department (English, math, science, history, etc.) must have a head, with additional curriculum responsibilities and meetings. Third, a disproportionate number of teachers at Peninsula are also professional development coordinators or union representatives — again, Peninsula has fewer teachers, so the denominator is far smaller. And finally, teachers frequently work hand-in-hand with counselors to support students on an individual basis.

“And I think, ultimately, what our students experience is that when they come to our campus, that you’ve got all hands on deck,” Llaguno said. “And when I say all hands on deck, it’s like, in a moment of time, whatever the situation is, there’s going to be probably five to six adults ready to support you.”

But that level of support is unsustainable for the small staff at Peninsula. For the first three weeks of the school year, Montoya — the sole wellness counselor at Peninsula — had 113 individual contacts with students. In contrast, Capuchino High School, with four wellness counselors, had just 72 contacts in the same time span.

“I think the quality of what we would do or what we’re already doing for our students would be even better [with more support],” Llaguno said. “You get stretched so far thin that sometimes you wish you could have the time to be able to do things with more intent.”

Llaguno and Montoya are omnipresent liaisons at the school between students, staff and administrators. They collaborate with faculty on a daily and hourly basis to support the individualized needs of students in an attempt to create the most conducive environment for learning.

At the end of the week, when Llaguno and Montoya sit back and reflect on Fridays, they realize the scope of their workload.

“It’s day in and day out,” Llaguno said.

Speaking before the San Mateo Union High School District Board of Trustees at a Jan. 20 meeting, Franco Sacdalan, a senior at Peninsula, pleaded with the district to support teachers at Peninsula in the same way that his teachers have supported him.

“They’ve helped me achieve a lot of stuff, and they give us a lot of help and resources,” Sacdalan said. “But I feel like they also need resources that they were not given, and the school or the Board did not provide for them.”

Leaver and Sacdalan encapsulate the contradiction that is Peninsula: even as the school faces a shortage of resources, staff and space, students often reported similar or higher scores on the 2019-2020 Healthy Kids Survey than the average student in the district.

Across the district, an average of 65% of students either agreed or “pretty much” agreed that they had a highly caring adult at school. At Peninsula, this number increases to 68%. In another example, 93% of Peninsula students never felt afraid of being beaten up at school; 90% of students in the district said the same.

This trend isn’t universal: 77% of students in the district say they have never been made fun of, insulted or called names, compared to only 70% at Peninsula. And just 59% of Peninsula students felt school connectedness in 2020, in contrast to 66% of district students. However, students had only kind words and praise for the school and staff.

“I would say this is the best school I’ve ever been to. I can say that hands down. I’ve never met more welcoming teachers. They’re like my friends,” Leaver said. “They really do genuinely care about you.”

Leaver feels her guided studies teacher truly knows her because she is comfortable enough to open up about topics unrelated to academics. She got off on the wrong foot with a different teacher, but now they joke about their arguments and disagreements. She feels the same level of comfort and ease with administrators.

“I’ve never been able to joke around with the principal before,” Leaver said. “It’s really a community more than a school.”

Sacdalan spoke in similar superlatives about Peninsula.

“From day one, since I came to Peninsula, it changed my life,” Sacdalan said. “I probably wouldn’t even be here right now if it wasn’t for the staff and the teachers who helped me be who I am today.”

Even if they can’t force the district to provide adequate resources for students, staff will continue to advocate for their school. They will lead by example, teaching students to stand up for themselves.

“We really try to show our students how to make lemonade out of lemons,” Montoya said. “We even have a lemon tree on campus to remind us.”