One year after weight room controversy, women get a fairer slice of March Madness

Prior to the 2022 March Madness tournament, the NCAA limited March Madness branding solely to the men’s tournament.

April 22, 2022

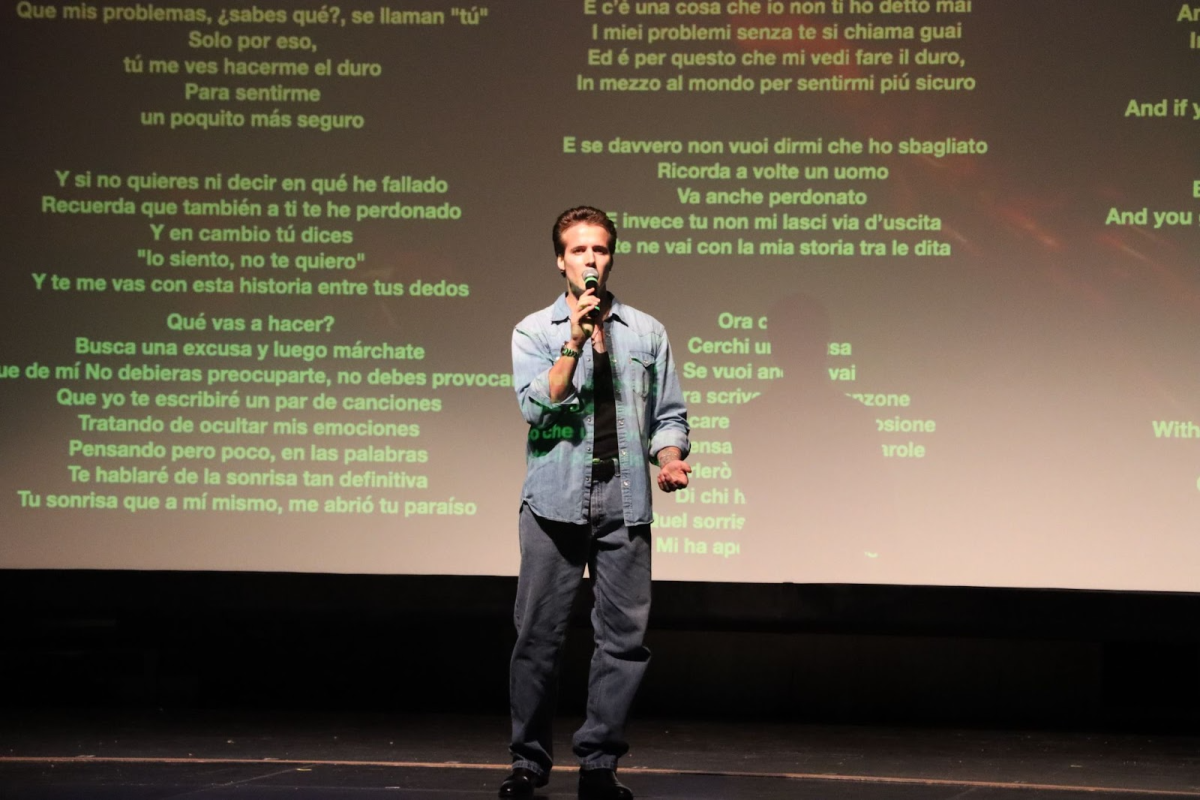

Millions saw, perhaps you among them, the jarring photo circulating social media last March ahead of the NCAA Division I Women and Men’s Basketball Tournaments.

The photo dichotomized the women’s and men’s weight rooms side-by-side: the women’s tournament weight room with a measly single set of dumbbells and the men’s tournament weight room decked out with rows of weights and training equipment.

I first saw the weight room disparity through that post shared by 2020 Burlingame alum, and my former basketball teammate, Sam Kershner on Instagram. It was originally posted by her cousin Ali Kershner, former Stanford Women’s Basketball sports performance coach.

Initially, it shocked me to think that such inequity could manifest itself in 2021 — especially in a multi-billion dollar enterprise like the NCAA and with the existence of the federal civil rights law Title IX, meant to prohibit sex-based discrimination in education programs.

“These women want and deserve to be given the same opportunities,” Kershner wrote in her post. “In a year defined by a fight for equality, this is a chance to have a conversation and get better.”

In a dignified response to a situation sparking national outrage, TikTok star and University of Oregon standout Sedona Prince further spearheaded the conversation by exposing the plentiful unused space in facilities, contesting the NCAA’s statement that the disparity in amenities was due to “limited space.” The video has been viewed 18.3 million times on Twitter and 12.2 million times on TikTok.

Overnight the NCAA responded by installing a beautifully lit room refurbished with racks of dumbbells, weight benches and other equipment — but the damage to its image and letdown to women’s basketball as a whole had been done.

One year on, the NCAA has made lasting changes to reform the viral embarrassment that also included other inequities in virus testing and food.

I have not yet mentioned “March Madness” once in association with the women’s basketball tournament, because previously the brand was only reserved for men’s teams.

That’s one of the most noticeable modifications the NCAA has made: the simple acknowledgment that women have a place in their lucrative brand. The NCAA advertised the now 68-team tournament with the March Madness logo starting last September, including the distribution of identical gift bags to men and women, hiring new employees to increase the women’s tournament staff and allocating equal payment for the women’s tournament referees.

The changes came after a gender equity review of the NCAA by the law firm Kaplan Hecker and Fink LLP following the issues in the 2021 championships. The report urged the merging of the men’s and women’s Final Four into the same city, criticized its previous advertising and found stark differences in funding. Over $1.5 million more was spent on ads for the Men’s Final Four last year than the women’s competition.

While the two Final Fours were not held in the same city this year — the women in Minnesota and the men in Louisiana — the amenities were adequate with players and coaches satisfied. And that, I’m here for.

But I want to address the number, “1.5 million.” I’m not oblivious to the fact that the men’s game is more high-flying than the women’s. Men bring in more views, which means more revenue, and money trumps everything.

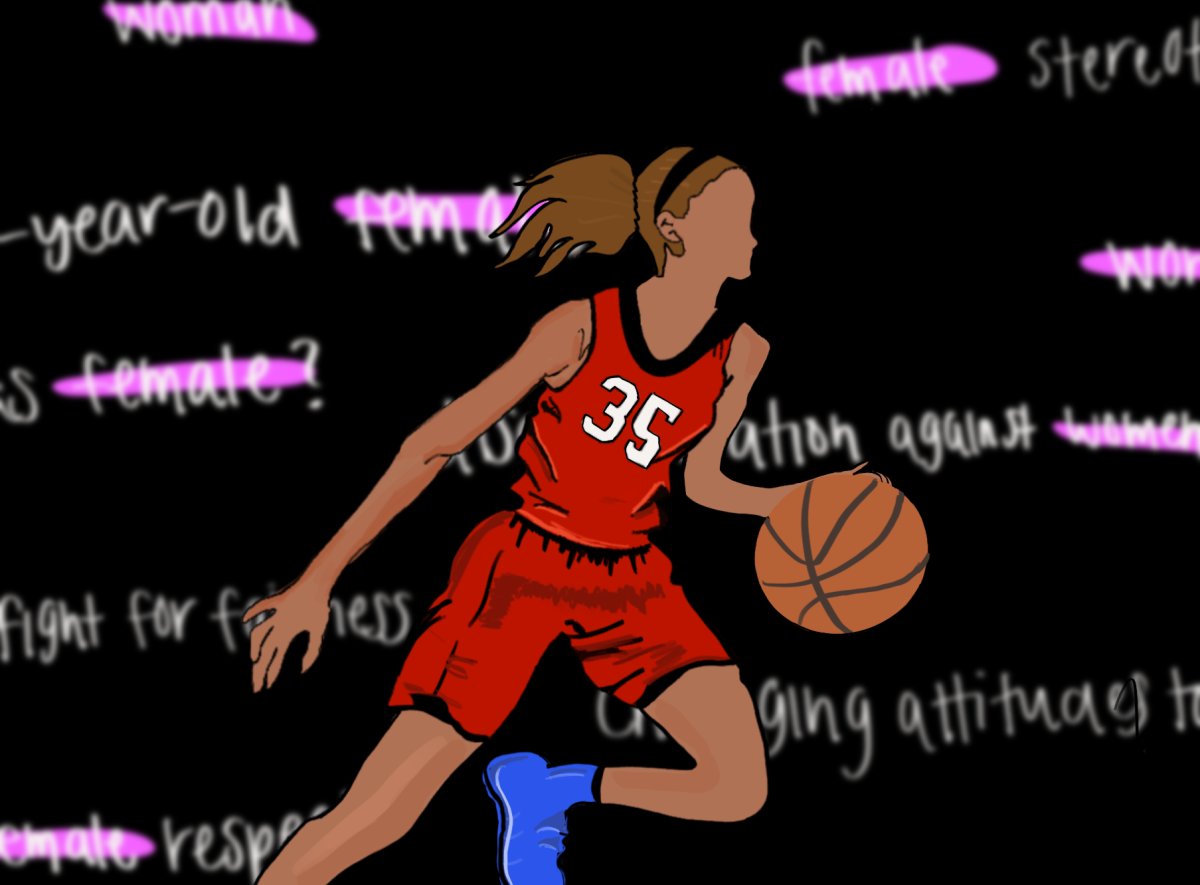

However, how can the game grow if you don’t invest in it?

“We’re in high demand, there’s a lot of people wanting to watch women’s basketball,” Dawn Staley, head coach of the 2022 National Champions, University of South Carolina, said to ABC’s Robin Roberts. “We’re in a place where we can definitely stand on our own as a sport, we just need the decision makers to invest. And I most certainly believe… they will get their return and then some.”

That “then some” was seen in the National Championship Game between the University of Connecticut (UCONN) Huskies and South Carolina Gamecocks. It was the most-watched NCAA Women’s Basketball championship game in nearly two decades, racking up 4.85 million viewers, up 18% from 2019, 30% from 2021 and peaking at 5.91 million viewers, according to ESPN.

It’s no coincidence that after the NCAA’s efforts to make a more equitable tournament, there has been a substantial growth in-person too, with 18,304 fans filling Minneapolis’s Target Center on April 3.

“This is just the start when it comes to improving gender equity in the way the two Division I basketball championships are conducted,” Lisa Campos, chair of the NCAA Division I Women’s Basketball Oversight Committee and director of athletics at The University of Texas at San Antonio, said in a press release last year.

That gives me hope, not only for the future of women’s basketball, but all women’s sports. Female athletes, coaches, administrators and fans deserve to see equity, and college sports are capable of setting that precedent. Little girls deserve to know the hardwood court doesn’t discriminate against anyone. Women everywhere deserve to know the bare minimum isn’t enough. The bar hasn’t reached its maximum height, so let’s continue raising it.

The NCAA’s response to their inexplicable mishap has been righteous. I just hope that no situation comparable to a weight room with 12 dumbbells will be the reason the right thing happens in the first place. And if it does, that response is the very same as this one.

Now, if you don’t mind, I’m still getting over Stanford University getting upset by UCONN in the Final Four.

Ms. Riley • Sep 15, 2022 at 12:05 pm

I appreciate your coverage of this issue. Thank you for drawing attention to it and keeping the conversation going.