To ban or not to ban? Surge in censorship sparks discussion over diversity in education

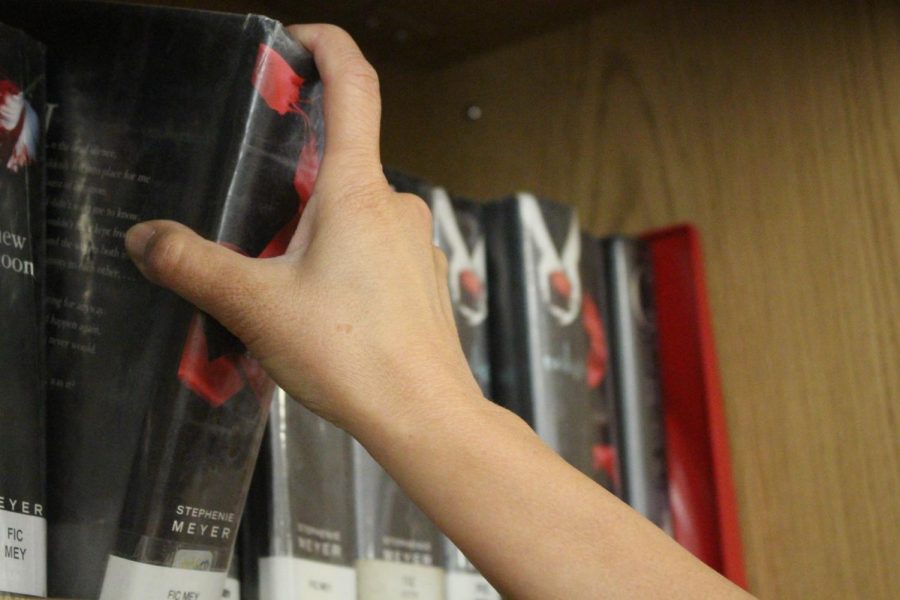

Although some books, such as the Twilight series, have faced bans and challenges in libraries across America, some schools choose to keep them accessible to students.

October 28, 2022

National Banned Books week, an annual campaign that celebrates the value of free and open access to information, ran from Sept. 18 to Sept. 24 last month. Although the seven-day campaign is over, book bans remain an ever-growing threat to American education.

In the first seven months of 2022, The American Library Association reported 681 attempts to ban books in U.S. schools. For the entirety of last year, that number only reached 729.

Book banning often targets certain opinions and ideas, restricting the variety of perspectives that students are exposed to. While school librarian Maurine Seto acknowledges that some think banning is necessary to limit youths’ exposure to inappropriate topics, she sees it as an effort to control rather than to protect.

“A lot of times people ban books because they just want people to think a certain way,” Seto said. “But I feel like the whole point of a library is that it allows people to research and look at different ideas.”

According to PEN America, a nonprofit that advocates for freedom of expression, banned content most commonly includes LGBTQ+ themes or characters of color.

“LGBTQ+ books have been banned from school libraries because parents were like, ‘Children shouldn’t learn about this at such an early age,’” junior Angelyn Liu said. “But they’re treating it as something that will taint their children, when in reality, it [won’t].”

Another reason books are often challenged or banned is due to misunderstandings or misjudgments regarding the content.

“What often seems to happen is that the people who are in charge of banning the books are not knowledgeable on the books,” English teacher Tim Larkin said. “So [they] either haven’t read it, haven’t studied it, or don’t know the context involved in it, and are almost never teachers.”

Although Larkin opposes censorship and removing books from school libraries, he acknowledges that there are some books that shouldn’t be taught, like Huckleberry Finn.

“[Huckleberry Finn] is a brilliant work literarily, structurally [and] rhetorically, but it uses the n-word [over 200] times,” Larkin said. “It’s very difficult to explain the context in which you can say this is a good work of fiction, but it’s very problematic.”

While book banning focuses on reading’s negative influences, Burlingame teen and children’s librarian Jenny Miner sees books as tools for good.

“Books can serve as windows where you can see into another world that you don’t identify with, and that’s important for developing compassion and empathy,” Miner said. “[You can] see yourself or see, ‘Oh, here’s an experience I would never have.’”

Liu suggested that instead of steering children away from certain topics to “protect” them, it would be more productive to encourage open discussions where they can further develop their own opinions.

“[Banned books] usually contain really important messages and oftentimes the reason why they’re banned is because people try to silence those important messages,” Liu said. “But we need to get them out.”