Students in understaffed businesses meet both unexpected pressures and benefits

Since the staff shortages of the pandemic, minimum-wage service industry employers have turned to teenagers to fill job vacancies. Students working in understaffed businesses have to juggle school work, personal lives and the atypical expectations of their jobs.

November 17, 2022

Truedan, a popular bubble tea shop in downtown Burlingame, hired senior Jayden Entenmann at the beginning of August. But by Entenmann’s third week on the job, Truedan was relying on a team of just four employees. And all of them were high school students — during the first days of the school year.

As Truedan drew closer to closing down, Entenmann started to work six-hour shifts. He claims it wasn’t necessarily an unwelcome development, but it did begin to impact his work-life balance.

“I knew it was an extra responsibility where I had to sacrifice other things in order to fulfill [it]. I wasn’t expecting to get rid of a lot of the free time I once had,” Entenmann said.

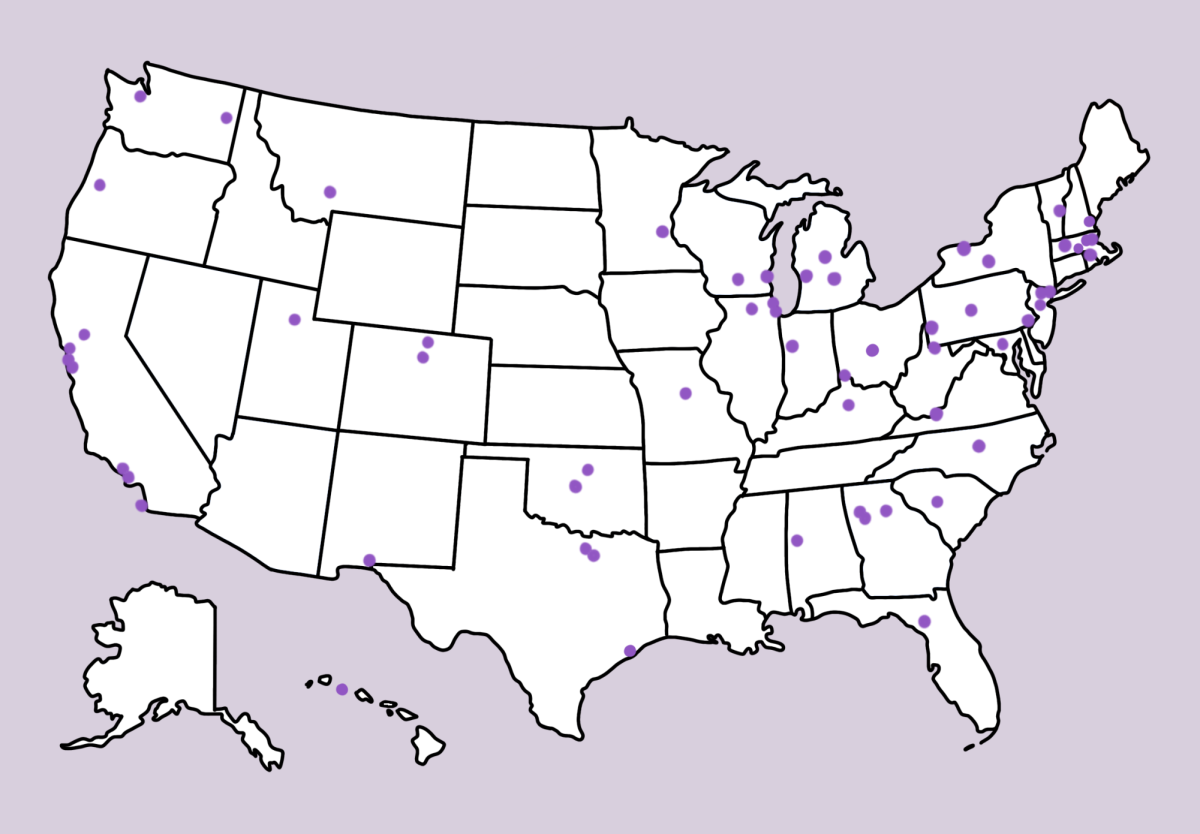

Entenmann isn’t alone. In the summer of 2021, 6 million teenagers across the country pursued summer jobs, resulting in the highest teen employment rates since 2008. According to a June report by the Pew Research Center, the post-pandemic teen employment rates were expected to continue to rise through the summer of 2022. As businesses and their employees recover from COVID-19, job vacancies have allowed teenagers to take up the mantle — but often, businesses are still understaffed.

Career coordinator Carrie Hermann noticed similar trends of employment and job searching in Burlingame. Hermann guides students in career exploration and intercepts hiring requests from local businesses.

“From what we understand, just from information in the community, it isn’t that easy to find workers,” Hermann said. “So I think there are companies that are expanding their search to include high school students.”

Senior Thomas Kim was one of those workers. He started working at Curry Hyuga when the restaurant was operating as take-out only. He worked there for six months and experienced the restaurant’s transition back into dine-in while short-staffed.

“I worked wherever they needed me. Sometimes we wouldn’t have enough people in the kitchen doing dishes, or we wouldn’t have enough house staff,” Kim said. “But I don’t think they were expecting to hire me; it’s because they needed staff. I was so young. I was 15.”

Curry Hyuga was Kim’s first job. Many students have similar first encounters with the workforce in minimum wage service industry positions. However, understaffed employers often lack the time and people to give their new workers space and time to adjust.

“They relied on me a lot more, even though I was a new staff,” Kim said. “They needed me to be completely consistent like throughout the first few weeks, instead of having that phase where you kind of mess up a lot.”

Entenmann noted the same shift in expectations at Truedan when the business started losing employees, even though he was a relatively new worker as well.

“There was an increase in work, not too dramatic… but it was odd to be doing like, 90 things [alone],” Entenmann said. “It got a little bit stressful when my manager started… pressuring me more, especially because we have so few workers and I have to do everything.”

Even so, students mentioned benefits to working in a short-staffed situation. With increased expectations and responsibilities, students have the chance to improve working habits and scheduling. According to Hermann, working can also help students build skills and valuable experience for moving forward in life.

“I do feel like my work ethic shot up significantly,” Kim said, referencing his time during Curry Hyuga’s return to dine-in. “I had standard six-hour shifts. They’d give me like 15-minute breaks. And then right after that, I just had to clock in again. It was a big difference from when I barely worked during Covid.”

Furthermore, students in understaffed businesses have a unique opportunity: a smaller team spends more time together, which opens doors for team bonding.

“[My co-workers were] a little bit more drained, but there’s also sort of like this camaraderie, because it’s just you and like one other person for a very long extended period of time,” Entenmann said.

Entenmann mentioned working alone for hours with his manager, an English-learner and recent immigrant, on some days. In that time, Entenmann gave her basic English classes. “We were closer because of that,” he said.

Ultimately, students reported a largely positive experience, or at least one that didn’t deviate too far from their expectations or goals.

“I wanted money…I wanted to work hard,” Kim said. “I think what I got paid for equally so it’s what I did, even if I didn’t always enjoy it.”

Jobs, Hermann acknowledged, are good but not mandatory experiences. She sees the decision as a largely case-by-case one. The skills gained in working, even those unique to understaffing, can also be found through community service and clubs.

“Students will have to look at their type of situation, they’ll have to decide, is this something that is okay with me?” Hermann said. “[Some students] might have to step away from that, but there may be other students who are able to, to balance it… and say this is just a learning opportunity for me.”