Why is hate speech a part of Burlingame’s vocabulary?

The majority of respondents to the poll reported they had heard slurs, offensive jokes and insults that degrade someone’s gender identity, sexuality, race, abilities, culture or ethnicity on campus.

On the morning of Nov. 17, staff found posters promoting anti-Semitism, white power, Adolf Hitler and the Aryan Freedom Network on campus. The news came less than a month after threatening, hateful graffiti was reported for the second time in a boys’ bathroom.

In an effort to report on how hate speech impacts students on a regular basis, the Burlingame B conducted a poll with over 70 student responses.

74.6% of respondents felt that hate speech is normalized at school. 93% of respondents hear some form of hate speech at least once a week, and 49.3% of respondents have been a victim of hate speech.

The majority of respondents also reported they had heard slurs, offensive jokes and insults that degrade someone’s gender identity, sexuality, race, abilities, culture or ethnicity at school before.

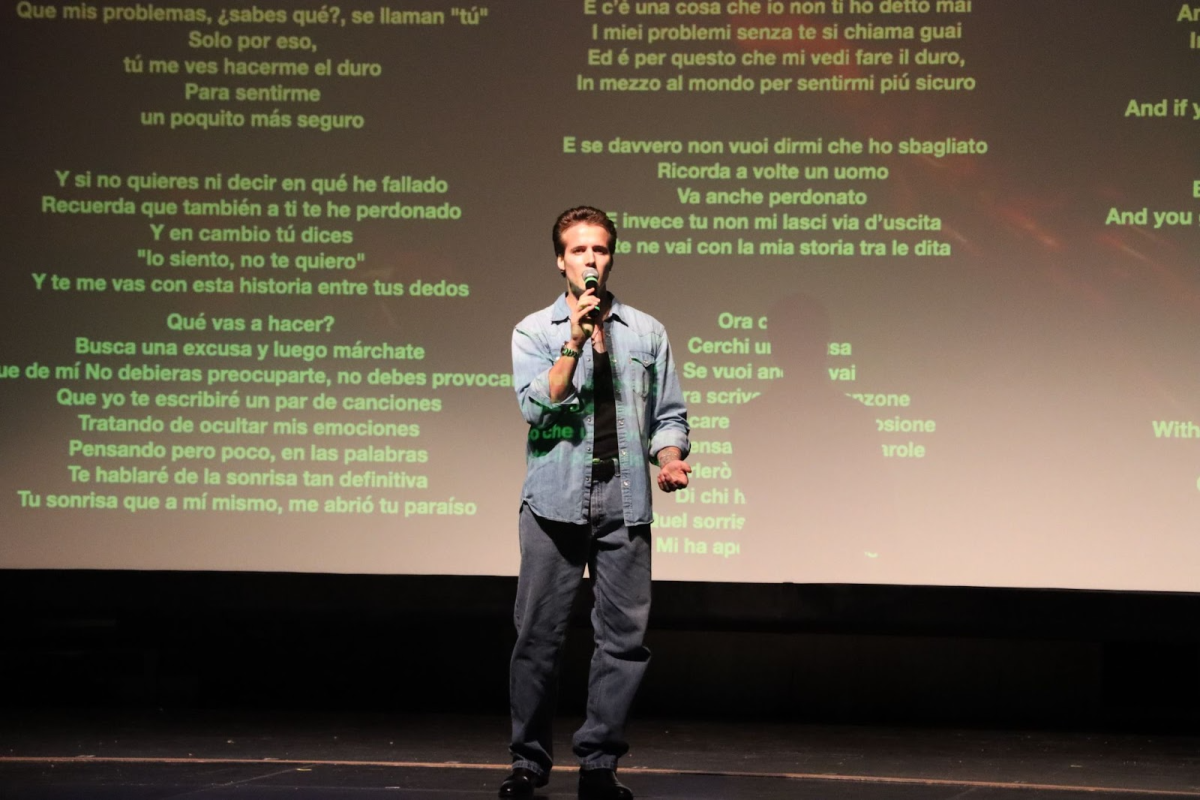

“Too many times to count.”

That’s what an anonymous student wrote in our poll when asked to explain an incident where she was degraded based on her identity. She said that she experiences microaggressions about being a girl 3-4 times a week and hears racially-motivated comments one or more times a week.

“Whenever I’m on campus (especially during lunchtime) it’s impossible to escape offensive slurs such as the R-word which other students often use as jokes,” another anonymous student said in response to the same question.

In contrast, a few students wrote off hate speech as jokes that don’t matter.

“Most of my friends joke around and say stuff, but they don’t mean it,” an anonymous student said.

However, other student responses emphasized that microaggressions and slurs degrade people’s identities. Various students recalled instances of antisemitic, homophobic and racist behavior from both fellow peers and teachers.

This aspect of school culture doesn’t end when the bell rings — students reported that hate speech exists on sports teams and in peer groups as well. Senior RJ Hunsaker, for example, played on the football team for two years and said it wasn’t a very inclusive space.

“In the case of LGBTQ[+] stuff, [the football team wasn’t] very friendly, especially some of the seniors last year,” Hunsaker said. “That was a little demoralizing.”

Freshman Kaylee Hwang felt more affected by hate speech at her middle school. Luckily, nobody has directed hate speech at Hwang in Burlingame. However, she does overhear it.

“I’m just surprised people take it as a joke,” Hwang said.

On the other hand, freshman Henderson Chan has unfortunately been the target of a hateful slur before. Similar to Hwang, he also overhears hate speech regularly.

“I’ve heard the N-word a couple of times today,” Chan said.

76.1% of respondents said students “never” or “almost never” actively work to prevent hate speech. Only 7% reported that students do so “all the time” or “almost all the time.”

Many believed that staff do a better job on handling hate than students, parents or other members of the community. Still, Hunsaker believes that more can be done about hate speech at Burlingame.

“I feel like a lot of it is swept under the rug,” Hunsaker said. “Or [student’s] simply just don’t care [about hate speech] unless it’s something high profile, like spray painting stuff, or the hate speech stuff in the bathroom.”

After the C-Building boys’ bathroom was found vandalized on Aug. 30, Principal Jen Fong and the administration launched investigations to discover who committed the act of hate speech, and how to prevent something similar from occurring in the future. But ultimately, Fong said, students need to step up to make the school a more inclusive place.

“I do think that students casually use words that are hurtful, and they don’t have a place here at Burlingame.” Fong said.

The administration believes that providing students with bystander training could make victims of hate speech feel safer and heard. Bystander training teaches people to talk to the victim of hate speech instead of directly confronting the user.

“Sometimes it doesn’t have to be confronting whoever said whatever they said, because that can be challenging for people,” Fong said. “But just going over to the person that is being bullied and you know, saying, ‘Hey, I’m here with you.’”

Hunsaker agrees that bystander training will be effective in acknowledging victims of hate speech. He also notes that educating others on re-thinking what they say is another way to take action.

“Teaching people to think critically about any of the things they read about is a large part of eliminating bigotry,” Hunsaker wrote. “Many bigoted talking points spew misinformation that can be easily taken apart if we knew the facts and think critically.”

In the spring, the administration plans to host Breaking Down the Walls, a program that encourages students to get to know each other’s unique backgrounds and experiences. After hosting the program on campus last fall, the administration hopes that it will be approved once again.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Burlingame High School - CA. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Abby Knight is a senior and the Social Media Manager for the Burlingame B. As a third-year journalism student, Abby is thrilled to run the B’s social...

Sophia Bella is a senior at Burlingame High School and a dedicated fourth-year journalism student, thrilled to serve as this year’s editor-in-chief of...