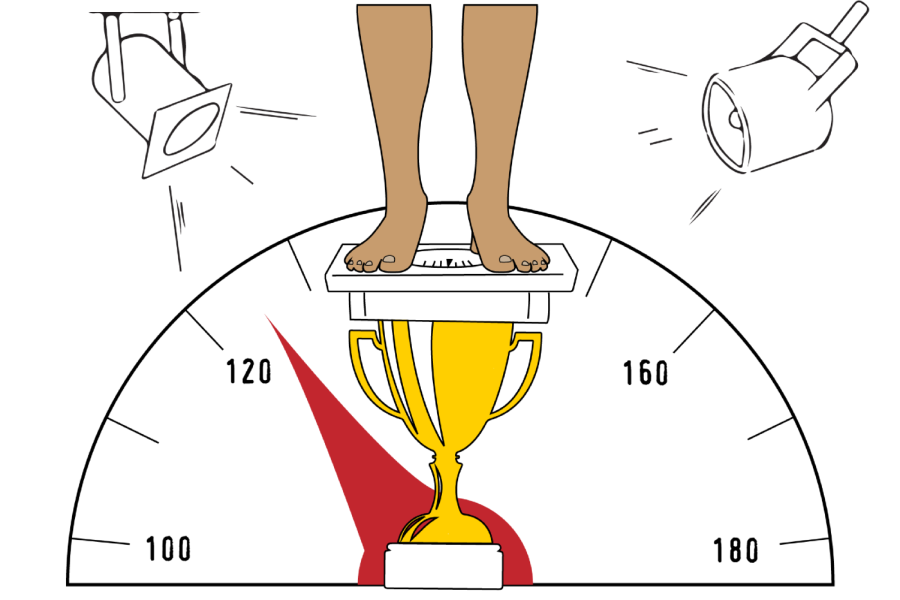

Weighing in

Despite new rules, weight cuts are still a harsh reality for high school wrestlers

Many point to the brutality of cutting weight as a reason for students turning away from wrestling.

In wrestling, depletion is a given: the sport forces athletes into taxing competition after weeks of dieting to meet a specific weight class. To succeed, wrestlers must push themselves to the limits of exhaustion.

It’s one of the reasons why participation in the sport, particularly in California, has decreased in the last decade from 27,634 in 2013, to 19,900 athletes today, according to a statistic from cifstate.org. This trend is evident even at Burlingame, where the wrestling team’s size dropped by half during the 2021-2022 season.

Some could say that this is just a result of the natural rigor of the sport; fewer kids in the new generation of athletes are up for the demanding wrestling-style conditioning. But in fact, the demanding nature of wrestling is actually what draws many to the mat.

“I like it because I get to push myself, and because I like making myself better, challenging myself and just being difficult to myself,” junior wrestler David Kracke said.

Instead, many point to the brutality of cutting weight as a reason for students turning away from wrestling.

The issue has not gone unnoticed over the past few decades, with several adjustments made to the weigh-in rules. Changes kicked into high gear after three infamous instances of college wrestling-related deaths occurred within a couple months of each other in 1997. But the problem persists: Between 1983 and 2018, 28 high school wrestlers died cutting weight.

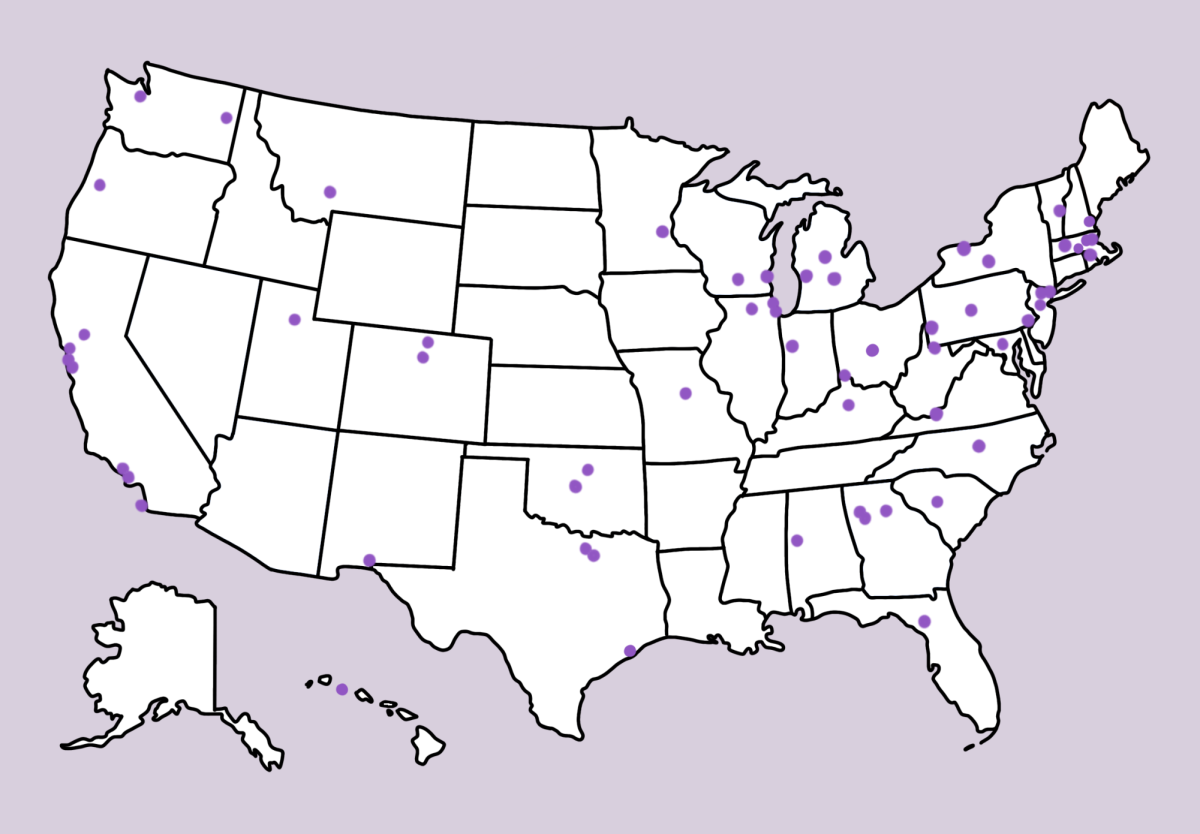

Now, many states, including California, have implemented a weight certification process. It begins before the season, where each wrestler gets assessed on their current height, weight and body mass index.

“You are then guided as to how much weight you can lose per week, per month throughout the season. This helps protect the wrestlers from over-dieting and dehydrating themselves,” said Burlingame’s head wrestling coach Ernesto Nuñez.

Lighter and leaner wrestlers have less body fat to burn off, and therefore can’t safely drop as much weight. Thus, the lower weight classes only have 5-7 pound differences between them. After winter break, each weight class threshold is increased by two pounds.

To discourage wrestlers from rapidly cutting for weigh-ins and then replenishing in the day before competition, weigh-ins can now only occur two hours before a tournament begins. Moreover, urine testing — which prompted wrestlers to dangerously diet instead of shedding water weight — has been removed from high school competition.

But perhaps the biggest change has been the stigma around weight cuts. In previous generations, it was a token of hardiness to maximize a cut, and coaches would encourage their wrestlers to do so in order to compete in certain slots. However, both coaches and wrestlers now avoid glorifying weight cuts.

“Those days are far gone,” Nuñez said. “I can’t tell my guys to wrestle at a certain weight, and ultimately the weight assessment gets the final say.”

It is now within a wrestler’s jurisdiction to decide how much, or if, they want to cut.

“You should be able to control your body because it’s yours. It may be hard, but if you really want to wrestle in a lower weight class, just run a little more and don’t be afraid to use your body,” Kracke said.

Ultimately, the weight-cuts and weight class rules can’t be eliminated or further loosened because they make the sport fair.

“It has to be strict because the best thing about wrestling is it’s a pound for pound sport,” Nuñez said. “It wouldn’t be fair if I had a kid who weighed 105 lbs wrestle someone who weighed 115 lbs, so it’s nice that everyone is in their proper weight class.”

Most Burlingame wrestlers have taken a mature approach, acknowledging the nature of wrestling competition and learning how to be safe in the process. But they still understand that the sport demands commitment — perhaps to an unhealthy level — from its athletes.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Burlingame High School - CA. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Zach is a junior in his first year on the Burlingame B staff. Outside of school, he spends a lot of time playing Football and Basketball, both within BHS...

Jackson Spenner is a Senior at Burlingame High School and a third-year journalism student. With a meticulous eye for detail and a passion for deep investigation,...