How self-esteem becomes dependent on the numbers on the scale

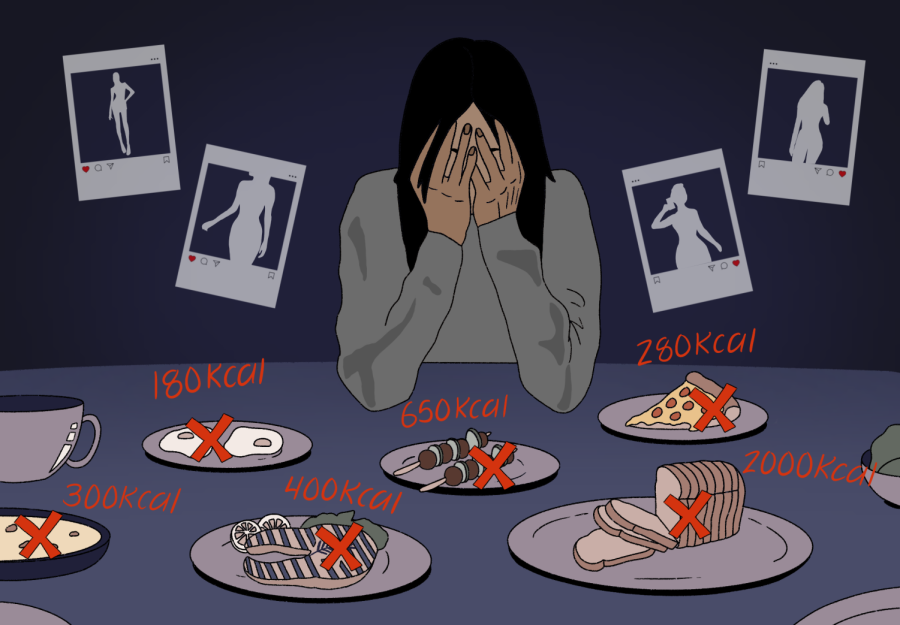

Teenagers experience pressure to conform to the unrealistic body types diet culture promotes, which makes them feel obligated to restrict their calorie intake.

April 8, 2023

Skip breakfast. You don’t need three meals in a day.

Run every morning. The fitter you are, the more popular you will be.

Look at these models on your social media. Don’t you want to be just like them?

Try laxatives and throwing up. You will get rid of all those calories.

Voices like these may overwhelm Burlingame students who struggle with body image, leading them to aggressively change themselves in order to meet unachievable beauty standards.

One Burlingame student, who wished to remain anonymous for privacy purposes, was plagued by thoughts like these. Wanting to adhere to beauty standards, she became determined to lose weight and, as a result, struggled with an eating disorder.

“There’s this constant worry about how you are supposed to look, what you should be doing with your body and if you are successfully holding up today’s beauty standards,” she said.

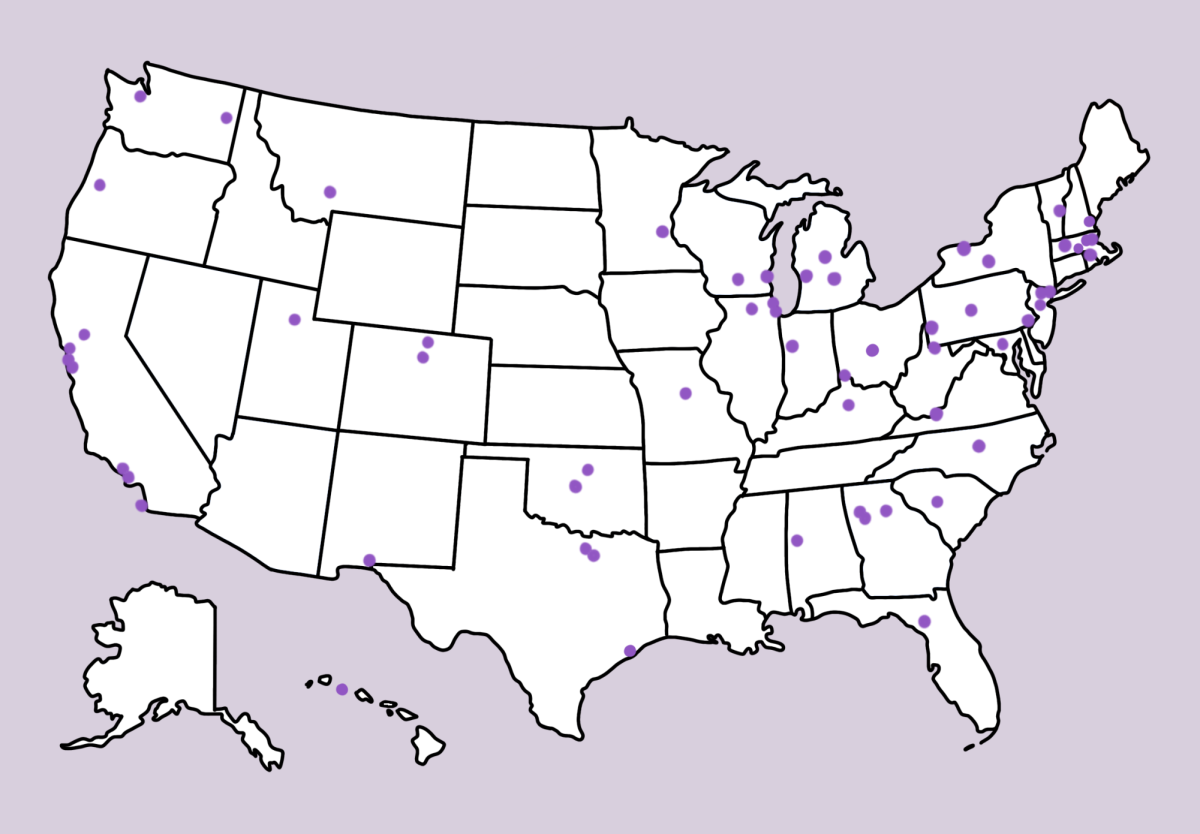

Diet culture, which glorifies thinness and labels “good” and “bad” foods, is pervasive throughout the United States, and especially among young people. By associating beauty and success with a slender figure, diet culture perpetuates the idea that eating in the “correct” way will result in the “right” body size — disregarding the pain, restriction, and negative health effects one must endure to achieve that.

Freshman Kaylee Hwang, however, came to realize that there is no “correct” diet or shape when it comes to people’s bodies. Eating a certain way won’t make anyone feel any better about themselves — especially when it’s eating in a way that conforms to the standards of diet culture. According to a study published by Insider, those who dropped 5% of their body weight over the course of 4 years were 52% more likely to be depressed than people who stayed within 5% of their starting weight throughout the same period of time.

“When I was recovering [from my eating disorders], I realized how wrong I had been this entire time,” said Hwang. “You don’t have to be the most perfect and skinny person, just be yourself.”

Nevertheless, diet culture permeates social media, advertisements, and, it seems, nearly every aspect of teenage life, making it extremely difficult for Hwang and other Burlingame students to ignore its misleading suggestions and the beauty standard it sets.

“That beauty standard is all around us,” said Hwang. “Pictures on social media, ads on how to lose weight or even comments from your family and friends about how you look.”

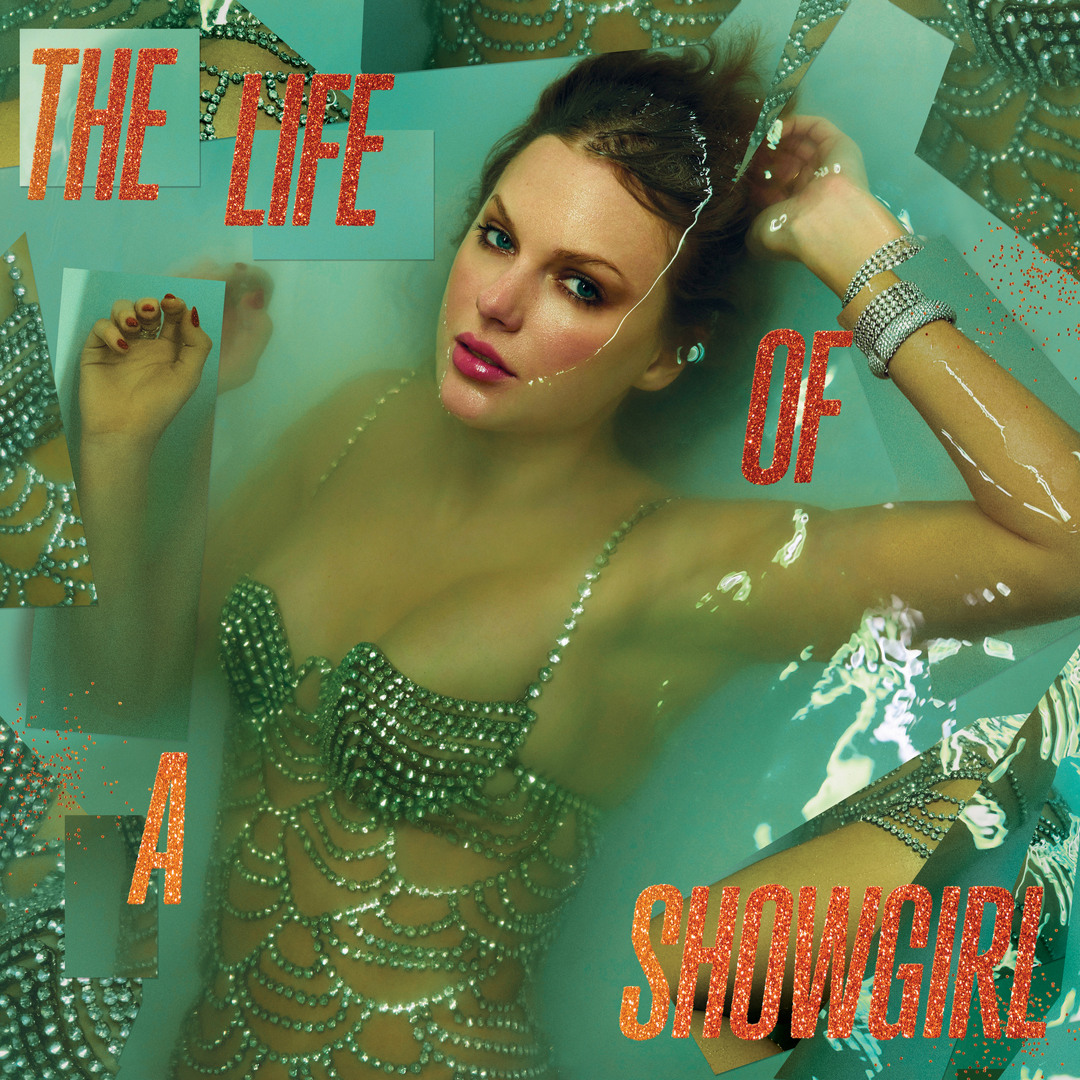

The ubiquity of social media only exacerbated such pressures, according to Hwang: She was bombarded with images, many of them doctored, of models with unattainable bodies. The pervasiveness of these images fed her the misconception that these bodies are “typical,” leading to a distorted understanding of what a healthy body looked like.

“I followed a lot of famous people like celebrities and models on social media. There were just so many pictures of these skinny, beautiful people,” said Hwang. “At one point, I began to believe that this was the standard body type and that everyone should [look] like this.”

The anonymous source mentioned above explained that over time, diet culture planted a seed in her head, telling her that she must mirror the skinny standard in order to be the best version of herself.

“I did not like the way I looked, so I thought that going on a diet would help with that,” she said.

But what had begun as a seemingly innocuous diet regime grew into a much more serious pattern of disordered eating for her. She became so determined to lose weight that she started skipping meals, sure that the fewer calories she consumed, the happier she would feel about herself.

“I had a bag in my closet that was full of uneaten food. When my dad made me breakfast, I would throw it away in that bag because I couldn’t bring myself to eat it,” she said.

As her condition worsened, her belief in diet culture only grew stronger. When she had lost a significant amount of weight, she received compliments on her appearance, further encouraging her adherence to diet culture.

“My family noticed my weight loss and complimented me. They would say, ‘You look so thin, you look so much better,’” she said.

In her middle school years, Hwang was diagnosed with two major eating disorders: anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Her situation became so severe that, six months into her struggle with these disorders, Hwang needed to go to the hospital because her body was so malnourished as to cause cardiac problems, putting her life in jeopardy.

“I had to eat more or my heart failures would continue,” Hwang said. “[The hospital] had certain meals I had to eat otherwise they’d put a tube through my nose to give me the nutrition.”

Even on the road to recovery, the anonymous source explains that the scars from the toxic beliefs imposed by diet culture haven’t fully healed, and the voice telling her to eat less continues to haunt her.

“I’ve definitely come a long way with my recovery,” said the anonymous source. “But there’s definitely always going to be that little voice in the back of my mind pressuring me to pay attention to my weight.”