Ethnic enclaves preserve the culture brought to America

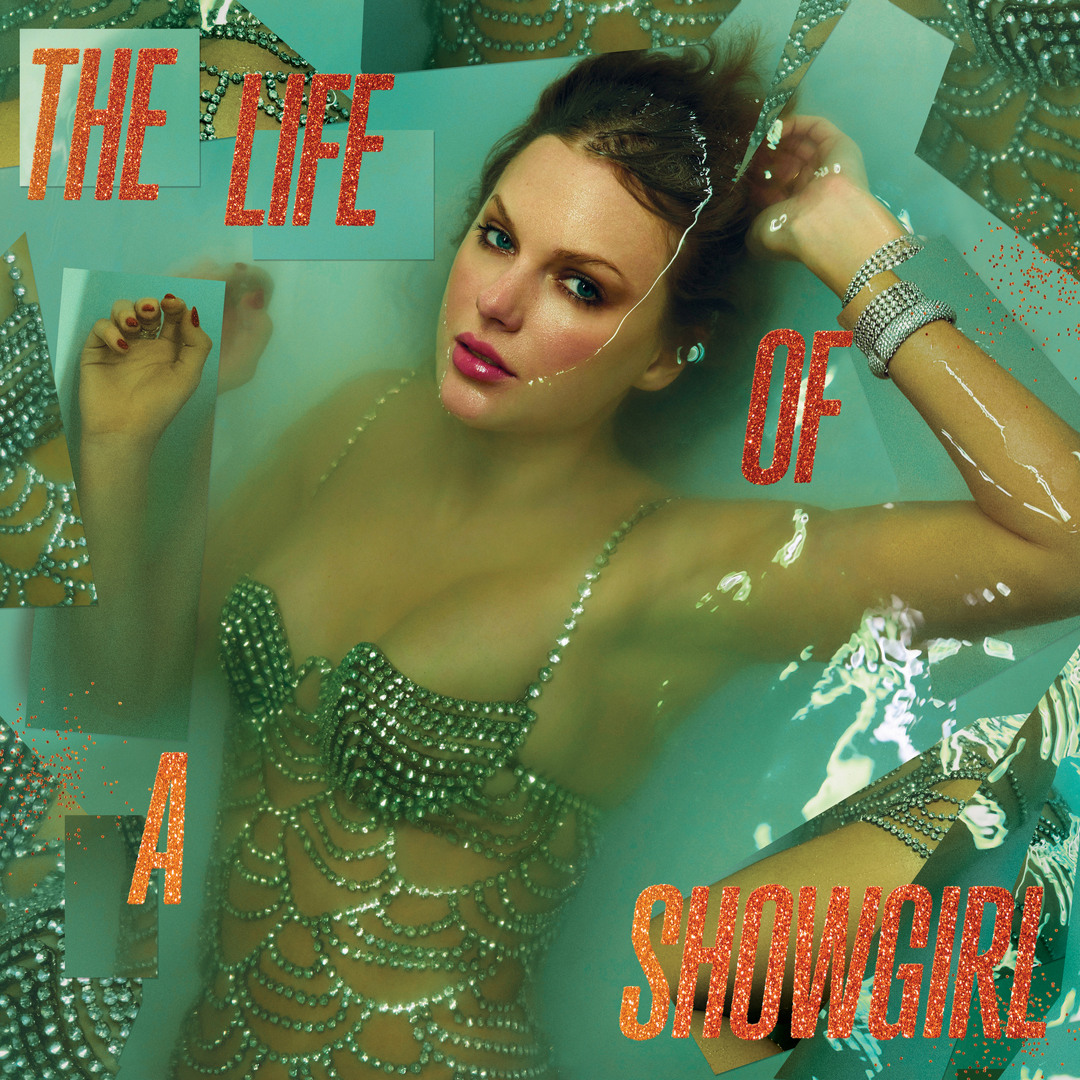

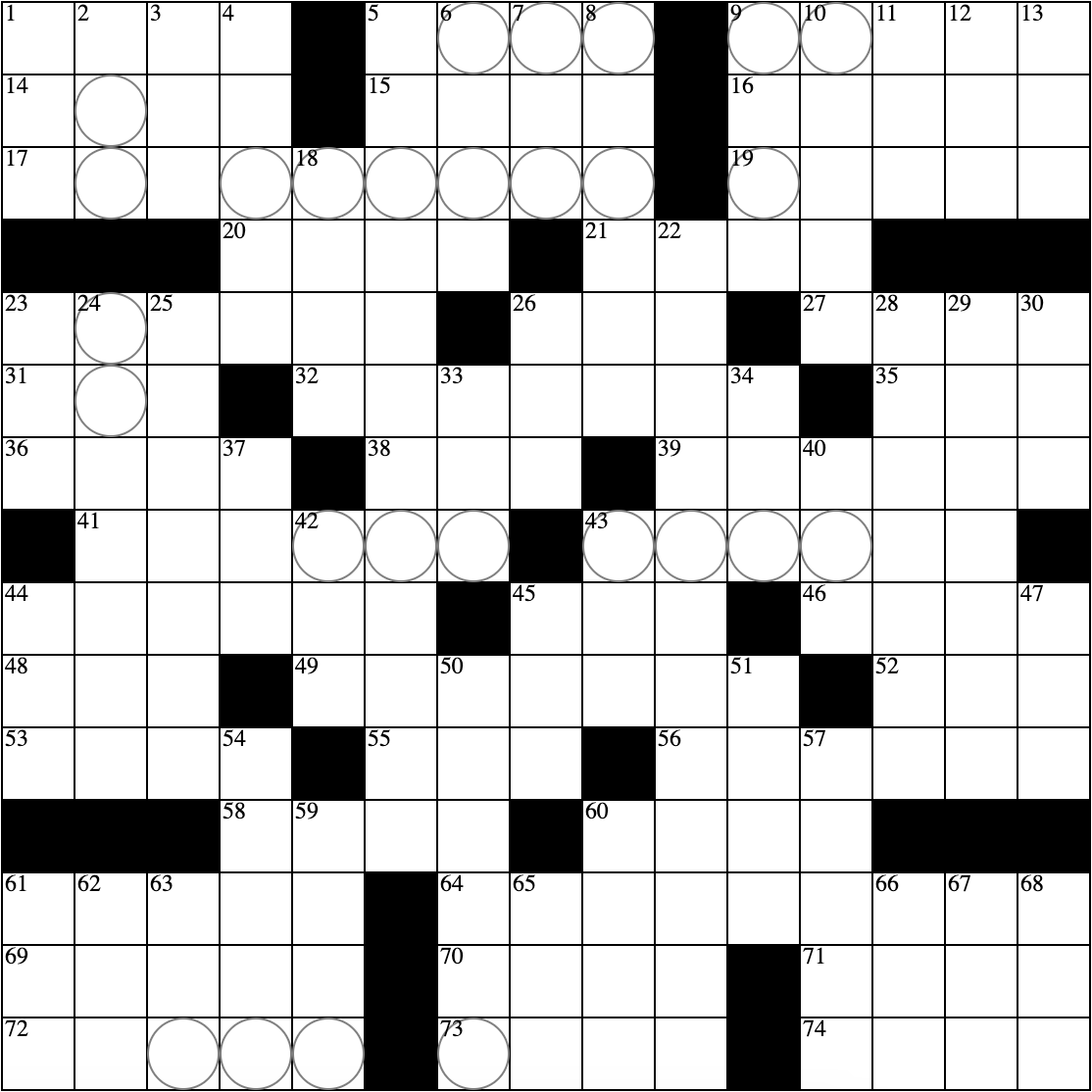

Photo Courtesy of Stacey Nolan

Hatsy and Moses Yasukochi showcase their bakery in Japantown, San Francisco in 1984 to honor their 10 year bakery anniversary.

April 24, 2023

America is full of ethnic enclaves dedicated to the culture of a specific ethnicity or race. An ethnic enclave is a region where a certain ethnic group resides and works. Still, in the words of my grandfather — a well-known figure in San Francisco’s Japantown — it’s also a place where culture is celebrated and honored. Ethnic enclaves honor the diverse ethnicities of America and how much they have overcome despite the government’s discrimination. These sacred places shouldn’t be overlooked but seen as a symbol of the American dream and the hard work of immigrants.

America’s prejudicial and racist government limited the success of people of color throughout its history. The Alien Land Law Act prevented Indians, Chinese, Koreans and Japanese from purchasing agricultural land, making it impossible to fuel their agricultural-based economy. When the Chinese immigrated to America during the Gold Rush in the mid-1800s, they were seen as inferior and excluded from the mining industry. Because of this repressive government, many ethnic groups were forced to create their own businesses within their own community, and thus the ethnic enclave was created. The ethnic enclave gave immigrants and ethnic Americans an opportunity to live out this American dream.

Since 1974, my grandparents, Moses and Hatsy Yasukochi, have cultivated a community with other Japanese and Asian Americans. My mother grew up dancing Japanese Kabuki, a classical form of Japanese theater with dance in the hear of Japantown, until her late 20s. Japantown allowed her to appreciate and connect with her culture while she lived in the Bay Area.

During World War II, my grandparents and their families were imprisoned in Japanese internment camps. When they returned from camp, they were left with nothing besides each other and a little bit of money. When they returned to San Francisco, they found a safe haven in Japantown. As Americans, they felt betrayed by their government and frustrated that they were seen as the enemy. My grandpa grew up in Japantown and 20 years later, he built a successful bakery with my grandmother. Today, they’ve been recognized as a semifinalist for the James Beard Food Award, a renowned organization that celebrates and recognizes culture within the cuisine.

As a young girl who visited the bakery often, I was exposed to an environment totally different from Burlingame. When I’d walk around the town, I would spot origami cranes dancing in every business window that whispered the Japanese legends of virtue, good fortune and longevity. As I watched tourists take pictures of the ubiquitous fountains, I stood with them, admiring the Issei and Nisei’s enduring strength and commitment. This became a new world for me beyond my home on the Peninsula. This small part of San Francisco was my family’s safe place. It is their home and their legacy.

“Even though they [ethnic enclaves] were founded on this basis of racism, the effect of them was incredible. The bakery and the business that me and my friends in J-town have created is proof of our hard work and Japanese pride,” my grandfather told me.

Because of America’s systematically racist society, Asian Americans were forced into these communities. But this segregation soon turned into a home and a true sense of belonging. These enclaves gave Asian Americans equal opportunities for success; they functioned as a transition into this new world for immigrants and would become their home for generations to come.

“After [my wife] Hatsy [Yasukochi] and I opened, I knew that the generations of children below us would be working here and sure enough, my three daughters would and so would their kids,” Yasukochi said. “Before I retired, I’d sit back in awe of their hard work, too.”