When swastikas showed up on the walls of campus bathrooms and Neo-Nazi posters started appearing in hallways, junior Emmett Kliger decided he had to do something.

At first, he tried to blow it off as a stupid joke. But then, things got worse.

“It all really happened because a friend of mine said something to me, that wasn’t hateful, but it was very ignorant,” Kliger said. “Ignorant about the Holocaust, ignorant about the antisemitism on campus.”

Kliger decided that he couldn’t wait for others to do the work— he had to take action and stand up for himself.

“I had to do something because if I didn’t I wasn’t sure who else would,” Kliger said. “There’s a big need to educate about both the Holocaust and the lead-up to the Holocaust because right now, there’s a lot of antisemitism. We need to educate so that we don’t repeat some mistakes of the past.”

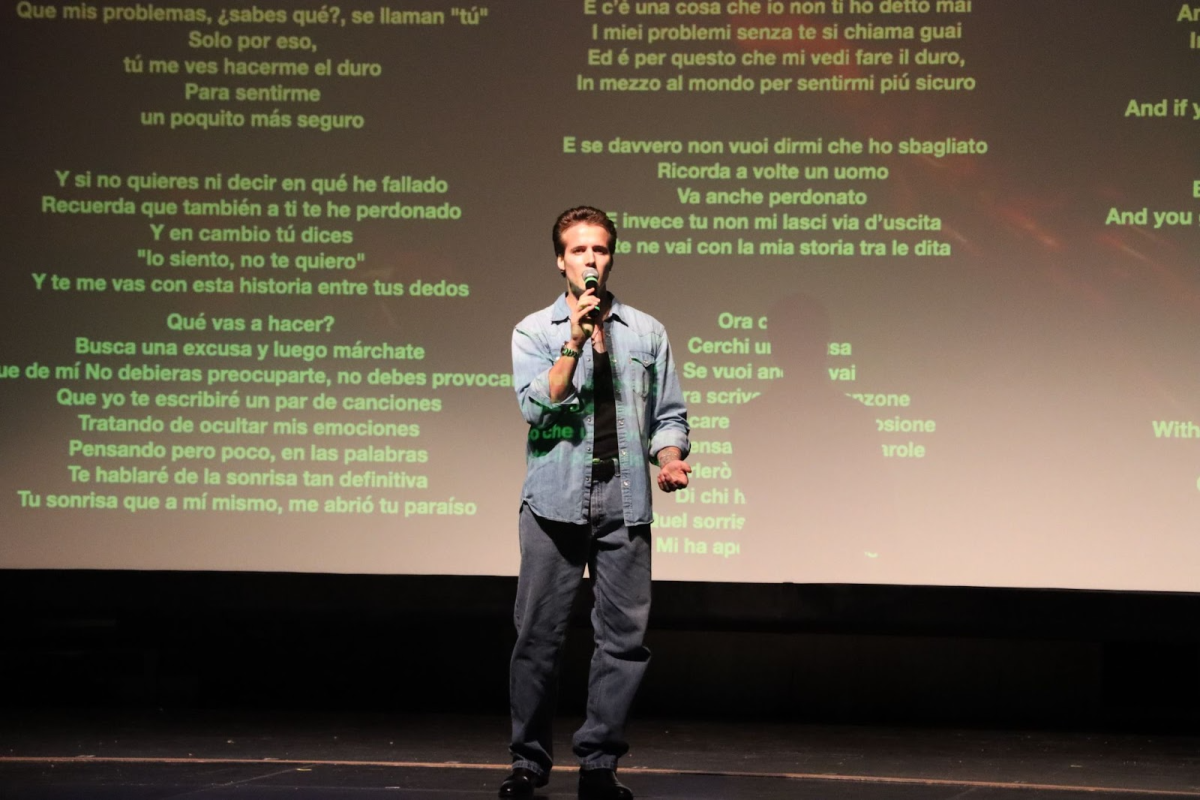

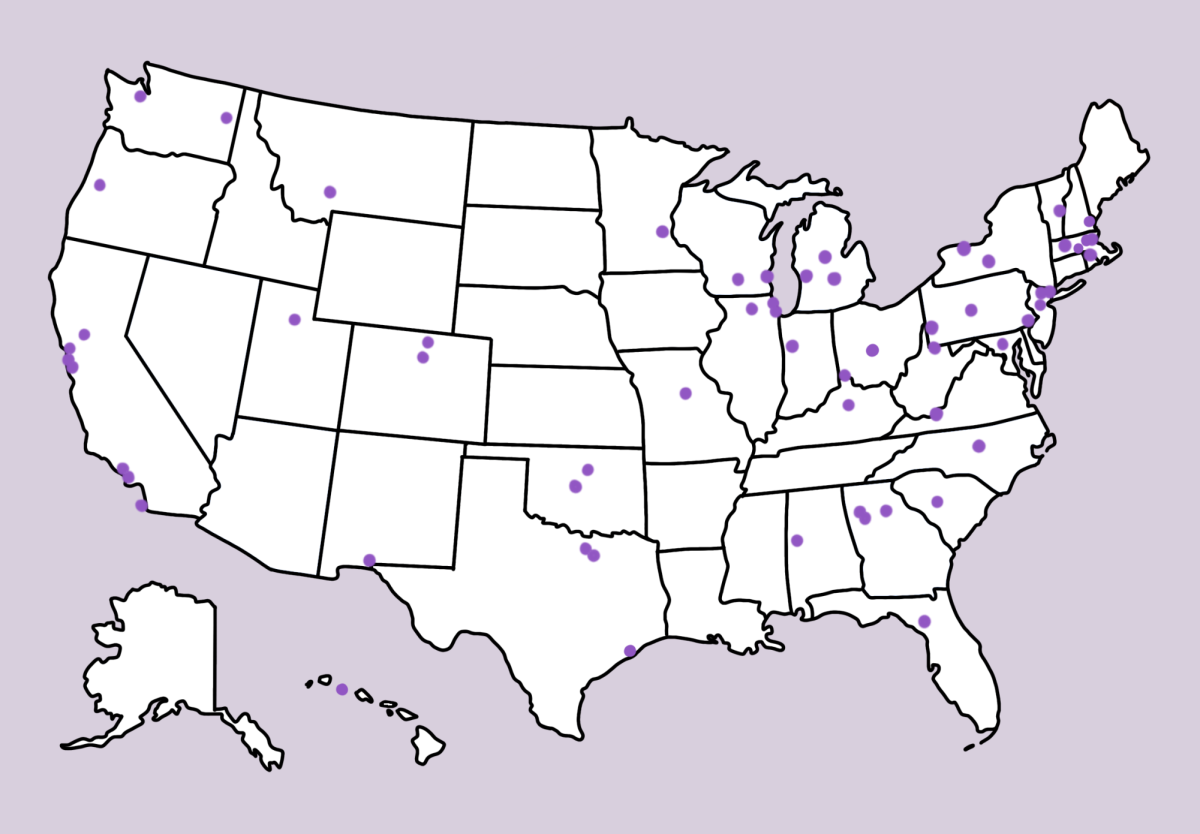

Kliger’s answer? The Antisemitism Awareness Project (ASAP), a nonprofit organization to combat hate in his community through easily scalable pop-up museum exhibits. They hosted their first exhibit at Peninsula Temple Sholom on Thursday, Nov. 9, and brought the experience to Burlingame on Friday, Jan. 26.

The exhibit starts by explaining the history of antisemitism and comparing antisemitism leading up to the Holocaust with antisemitism now. As a World History teacher, Jim Chin felt that this comparison stood out from the rest of the exhibit.

“Seeing these reminders, we like to think we’ve moved past it, but in a lot of ways it’s still an issue,” Chin said. “Maybe we’ve made some progress, [but] that doesn’t mean we should stop caring and challenging each other to be better.”

The modern examples in the museum not only included highly-publicized antisemitic statements but also community-specific examples, like when antisemitic statements were written on a locker in March last year. This was shocking, even for ASAP’s own Associate Director junior Audrey Colvin.

“It definitely opened my eyes to a lot of the bias that I don’t see because I’m not Jewish,” Colvin said. “I did not see a lot of the antisemitism that was happening in our community. There is a lot of it in Burlingame and just being a part of ASAP made me see that other side.”

Many visitors were moved by the message ASAP preached at the first exhibit at the Temple.

“A lot of people cried,” Colvin said. “There was this one woman, who came up to me, she was elderly, and she said that one of the men who smuggled Jews out of Germany during the Holocaust saved her mom. That was really powerful to see how this stuff affected everybody. ”

While one of the main topics of the exhibit is antisemitism, it also highlights hate in other communities as well.

“It did focus a lot on the Jewish experience, but it also included [examples of] Islamophobia, anti-Asian stuff,” Chin said. “In my opinion, it made sense [that] it included examples that also affected non-Jewish communities. There were a lot of valid ways to include as many communities as possible.”

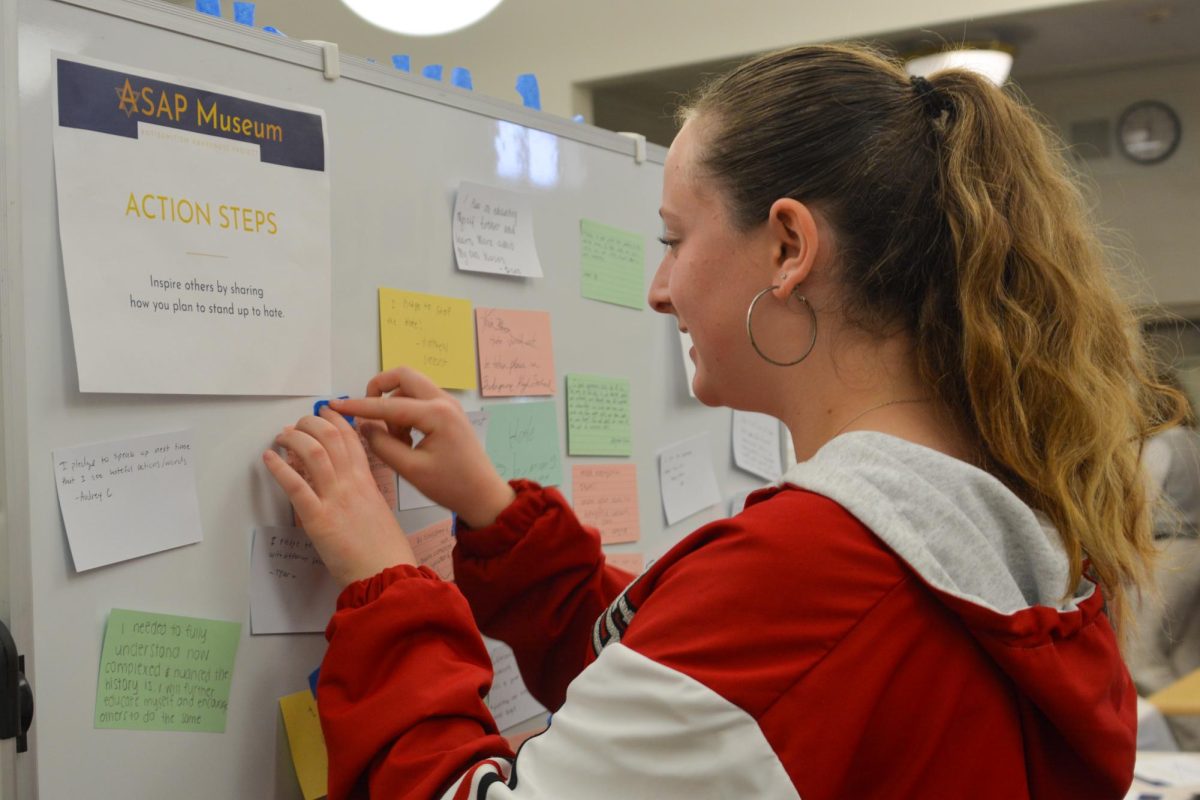

After the community-specific examples, they dived into the Anti-Defamation League’s pyramid of hate and offered actions visitors can take to fight hate in their community.

“I think the goal of that museum is not just to make you more informed, but to encourage someone to be more proactive in combating prejudice,” Chin said. “The end of the exhibit had resources for you. The museum’s focus on [key questions like] ‘what can we do with all this information?’ and ‘how can we use this information to be better citizen?’ is [a big difference].”

Despite administrative efforts to combat hate at Burlingame, teachers like Chin still notice and try to fight hateful comments.

“As a teacher, there’s always a temptation if I hear something [bad] in the hallway or in a passing period to pretend I didn’t hear it, but we can’t let that happen, that only makes it worse,” Chin said. “[We need to] confront it, [but not] in a hostile manner. You want to call it out, but in a way that gives people a chance to be better.”

But sometimes, when it comes from an adult, students won’t listen.

“I think it means something different to the student body when it’s students doing this rather than a bunch of teachers,” Chin said. “It was really important to include an example of that sort of stuff in our community, to point out that this happens in places where a well-intentioned but naive adult might not think it would happen.”

ASAP hopes that by educating other students themselves, they can fight hate through positive peer pressure.

“If we can empower students so when they see something that they know is not right, whether it be racial discrimination, antisemitism, homophobia or whatever, they feel empowered to do something because it’s a lot harder to be hateful when you have five, six seven, eight or nine people telling you it’s not okay,” Kliger said.

Kiger believes that while combating hate is challenging, ASAP can still make a meaningful difference, however small.

“Will we completely change who you are as a person? Probably not,” Kliger said. “But if we can turn someone from being apathetic to caring about fighting hate or putting it into action, that’s what we want to do. We want to push people in the right direction.”