When fifth-grade elementary school teacher Patricia Althaus saw her son Liam struggle to decipher the birthday card her mother had gifted him, stumbling through the loopy letters and skipping over phrases, she realized for the first time how insufficient the cursive curriculum is.

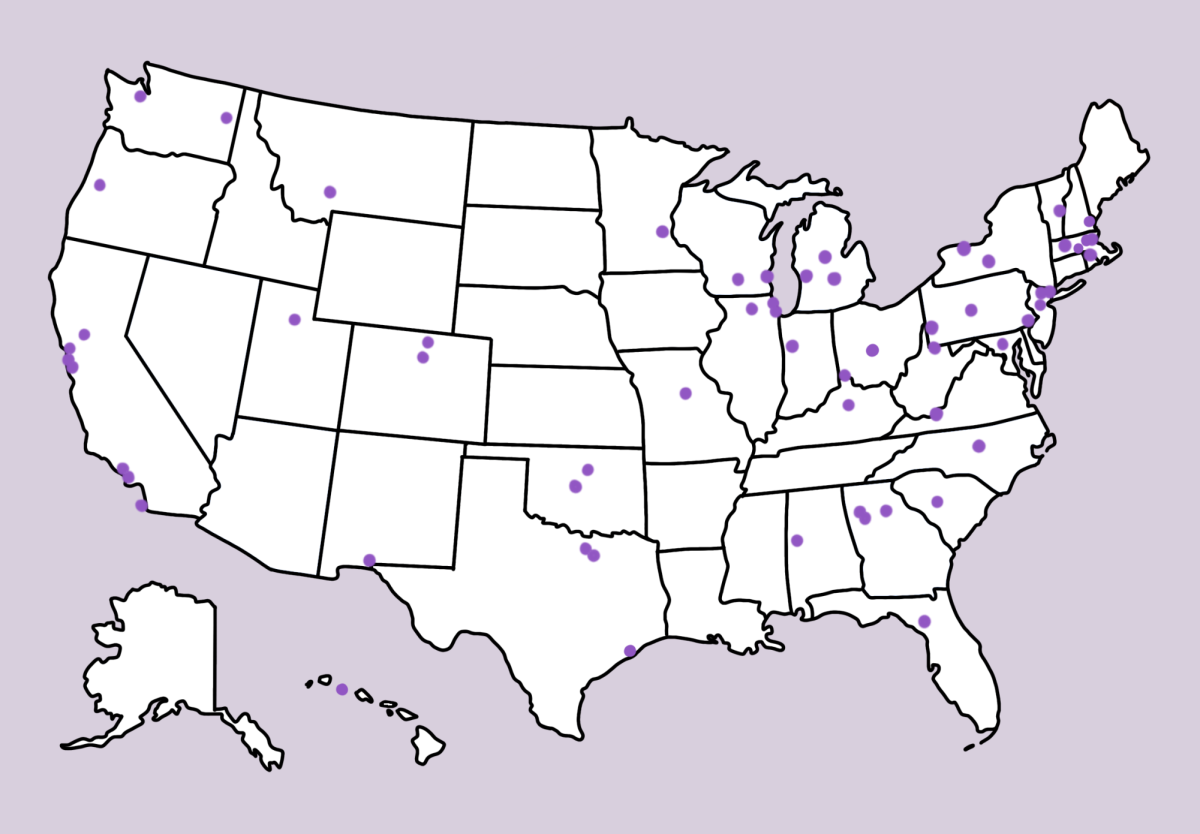

It seems that lawmakers across the state had the same realization. On Oct. 23, 2023, California joined the growing list of states that have made cursive compulsory in all elementary school curricula. AB 446 aims to equip the newest generations with essential skills — signing one’s name on important documents and analyzing historical documents, whether to understand America’s history or trace back one’s heritage.

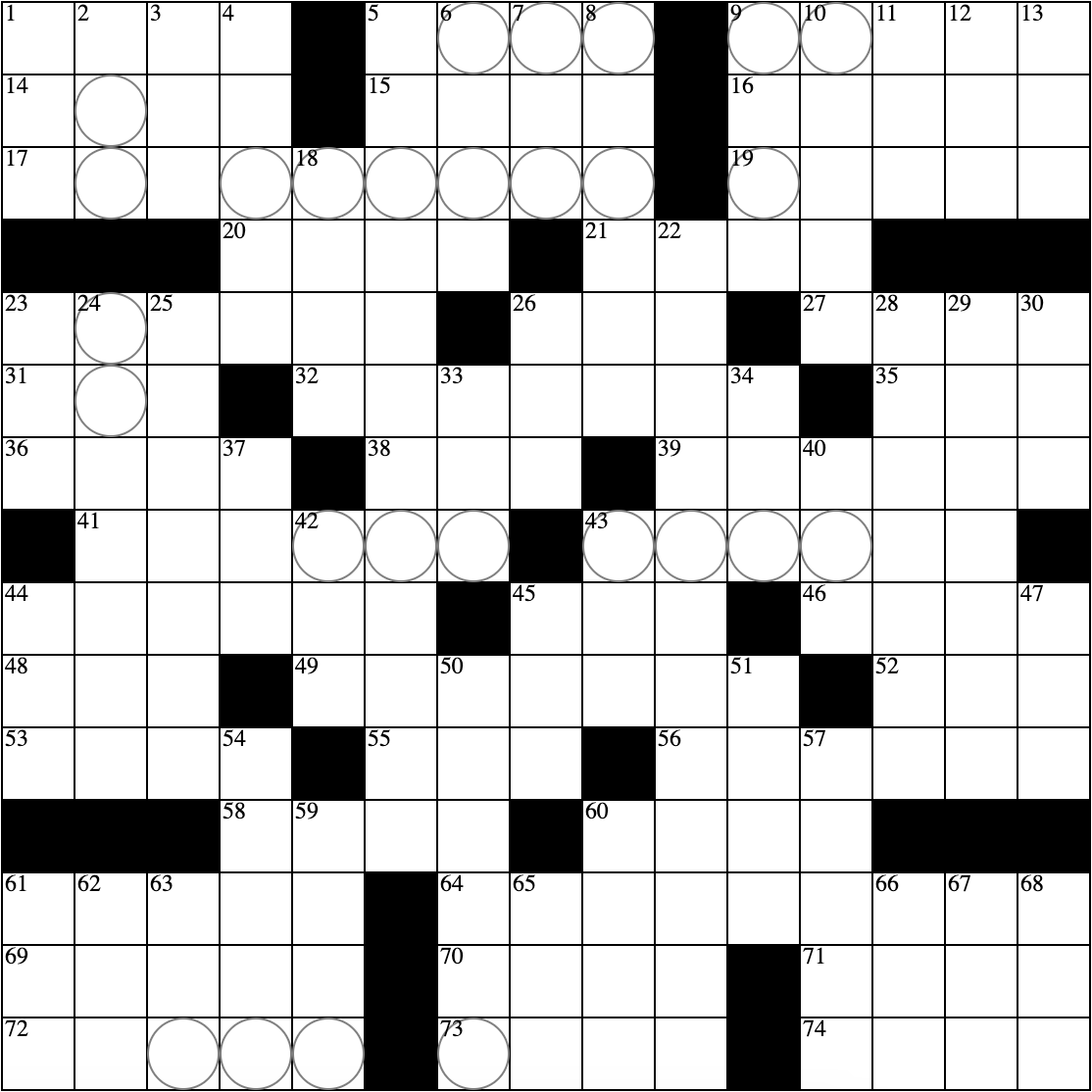

“When kids start to color, they always do circles. So the funny thing is, printing is what they’re forced to do, but kids naturally do circles, which is basically cursive,” fourth-grade elementary school teacher Susan Sawczuk said. “I’m not advocating adding cursive writing into kindergarten, but it’s natural for us to do cursive. The problem is we break that cycle, and then we force them to do printing. And then we go back again and they don’t have the muscle memory.”

Many teachers who have already been teaching cursive long before it was a requirement strongly believe in the psychological and academic benefits of the writing form. Fourth and fifth-grade teacher Kathleen Butler expects that her students write all handwritten work in cursive, but not without reason.

“I think cursive helps with creativity,” Butler said. “It helps with focus. I think you actually become a better speller when you are using cursive writing, because you start to think of it all as letters joined together rather than single pieces. From the spelling standpoint, it helps to make a stronger hand-eye coordination and the overall brain development is essential.”

An EGG-based study conducted at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology demonstrated the importance of cursive handwriting as a skill to help the brains of students learn and remember information faster and more efficiently. As schools rely more on technology for in-class assignments, students who are not required to learn cursive are now at a disadvantage, according to the study.

“These last thirteen to fourteen years, we’ve done a disservice,” Althaus said. “There’s this big chunk of kids who, going into adulthood, are not completely confident that they can read something their boss writes on a sticky note. Not everything will always be communicated via email.”

APUSH teacher Annie Miller, similarly, has noticed an inverse relationship between one’s technology use and the quality of their penmanship, signifying a need for cursive in curriculum.

For Miller, cursive holds a special place in her heart as it allows her to read the journals left by her deceased mother, who learned cursive through strict Catholic School teachings.

“A life skill, professional skill and academic skill is that we still have some form of legible handwriting that people can read,” Miller said. “Personally, I don’t care if it’s cursive, block letters or script, as long as I can read your handwriting. I’m noticing the more and more people type, the less legible our handwriting is. If cursive is going to help with that, awesome.”

But cursive’s benefits extend beyond the classroom. Consider a signature — whether it’s a quick scribble on a receipt or signing a legal document, a signature encapsulates a person’s identity and represents them on paper.

“When I look at everyone in my classroom, I don’t think there’s any two signatures alike,” Butler said. “If I pick up a piece of printed work, I don’t know if I’d be able to tell who’s is who’s, but if I look at a piece of cursive, I know it’s so and so’s without even reading the name. It’s very distinct. It allows students a little bit more creativity and individuality.”

To Evan Liu, a fourth grader at Spring Valley Elementary School, cursive seems like an unnecessary skill for his future in society.

“I don’t see my parents use it, and they don’t know that much about it,” Liu said. “[Cursive] is harder to write and it’s more complicated. It feels like a chore because it takes more time.”

While California’s new law may seem promising for cursive advocates, state policies are constantly changing, leaving teachers in what Sawczuk describes as a “pendulum.”

“You have people who are not in a classroom or have been out of touch for twenty years that issue these laws,” Sawczuk said. “That’s what a lot of people don’t understand. It’s not just what law is mandated, but what’s best for my child. What’s best for the students in my class?”