Everyone is United: there was no Delta at SFO as a result of American shutdown

In November 2018, there were over 4.5 million total airport passengers that went in and out of SFO. According to an airport official, SFO did not experience any significant effects as a result of the government shutdown.

February 20, 2019

Contrary to stories of airport nightmares during the 35-day government shutdown, San Francisco International Airport (SFO) was relatively unaffected.

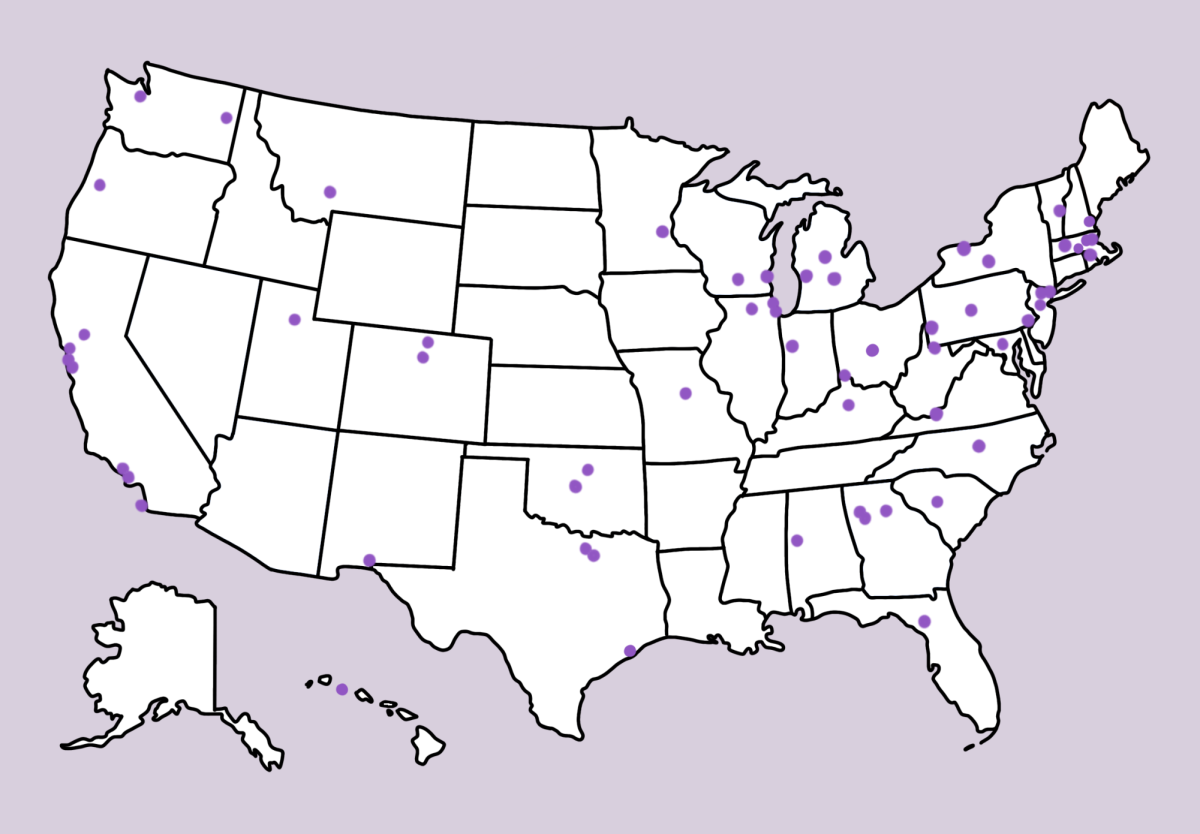

While U.S. airports across the nation, including Atlanta-Hartsfield and Houston, reported significant airport security (TSA) callouts and even closed some checkpoints, the Global Entry Enrollment Center was the only department closed during the impasse at SFO. The office employs Customs and Border Protection officials.

Over the course of the shutdown, caused by a stalemate between Democrats and Republicans over President Trump’s proposed southern border wall, 800,000 federal workers went without pay. One of the most closely covered departments by the news media was the TSA, which saw up to 10 percent of their workers call out sick due to “financial limitations,” compared to 3 to 4 percent at the same time last year. SFO, however, employs a private contractor, Covenant Aviation Security, to oversee its safety operations, so officials were still being compensated.

“The shutdown did not affect flight operations or wait times in security checkpoints or international arrivals facilities,” Doug Yakel, SFO’s airport information officer, said.

According to Yakel, SFO opted into the Screening Partnership Program (SPP) in 2005 with the expectation that “airports would eventually return to a privatized model” after 9/11, when the TSA was created. Although there are several other airports nationwide that use SPP, SFO is the largest.

That being said, air traffic control officials at SFO were not being paid during the shutdown. While Yakel cited no significant staffing shortages, controller Frederick Naujoks told KQED on Jan. 11 that some of his colleagues were seeking other jobs after-hours.

“I’ve even had a couple of people come to me and say that they want to work for Lyft or Uber in addition to coming to work and working air traffic,” Naujoks said.

Rick Maldonado, a junior, traveled in and out of SFO during the shutdown on his trip to Mexico.

“Everything seemed exactly the same,” Maldonado said, “but I was a bit tired.”

Airports were not the only places affected by the shutdown, even though they may have received the most coverage. National parks suffered from staffing shortages and some closed facilities; a recent Smithsonian article indicated that Joshua Tree National Park “could take 200 to 300 years to recover” after several emblematic trees were destroyed. After running out of reserve funding on Jan. 2, the Smithsonian closed all of its museums, including those on the National Mall in Washington D.C.

President Trump temporarily reopened the government for three weeks on Jan. 25, warning that if no deal was reached in Congress, he would consider declaring a national emergency. Such an action could theoretically allow Trump to unilaterally redirect funding for the border wall.

Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.), an outspoken critic of Trump and a 2020 presidential contender, said he was holding the American people “hostage.”

“They don’t need a wall. They need a paycheck,” Harris said in a floor speech on the 26th day of the shutdown. For now, workers who missed their paychecks are relying on Washington politicians to make a deal before the government shuts down once more.