How the Chinese Exclusion Act matters to Burlingame

People mill around in Chinatown, San Francisco. Established in the 1850s, Chinatown is a cultural center with a densely populated area with 15,000 residents and many tourists.

December 10, 2021

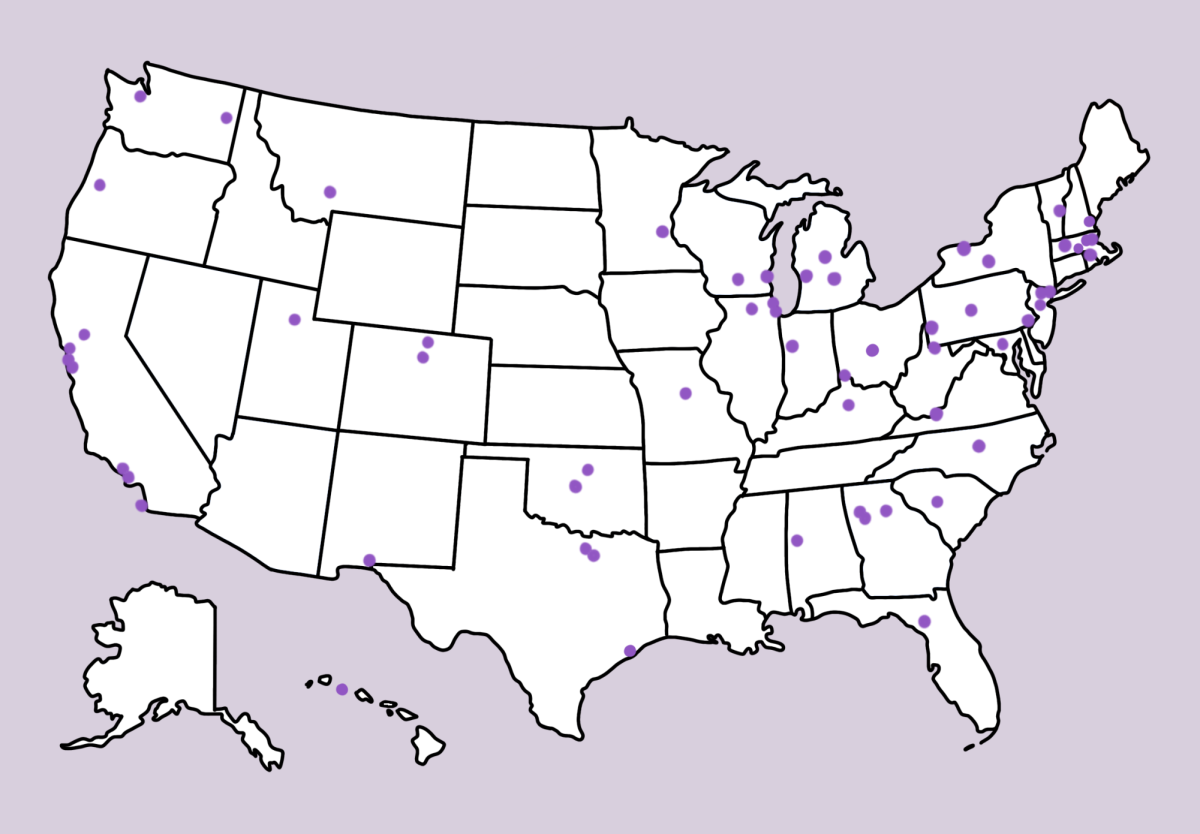

In the light of recent anti-Asian violence, many Californian communities took on a conversation confronting the past. The city of San Jose apologized to Chinese immigrants in September by acknowledging the history of violence, discrimination and the destruction of several Chinatowns. San Jose is one of the latest cities to apologize, following the first Californian city, Antioch, to do so in May.

A history of hate against Asians is especially prevalent in California, where racism fueled the creation of the Chinese Exclusion Act. Signed in 1882 by President Chester A. Arthur, the act suspended Chinese immigration into the United States and declared Chinese people ineligible for naturalization. The law was a response to the large influx of Chinese people into America — a trend that grated against white purity ideologies and induced fear from white laborers over job availability.

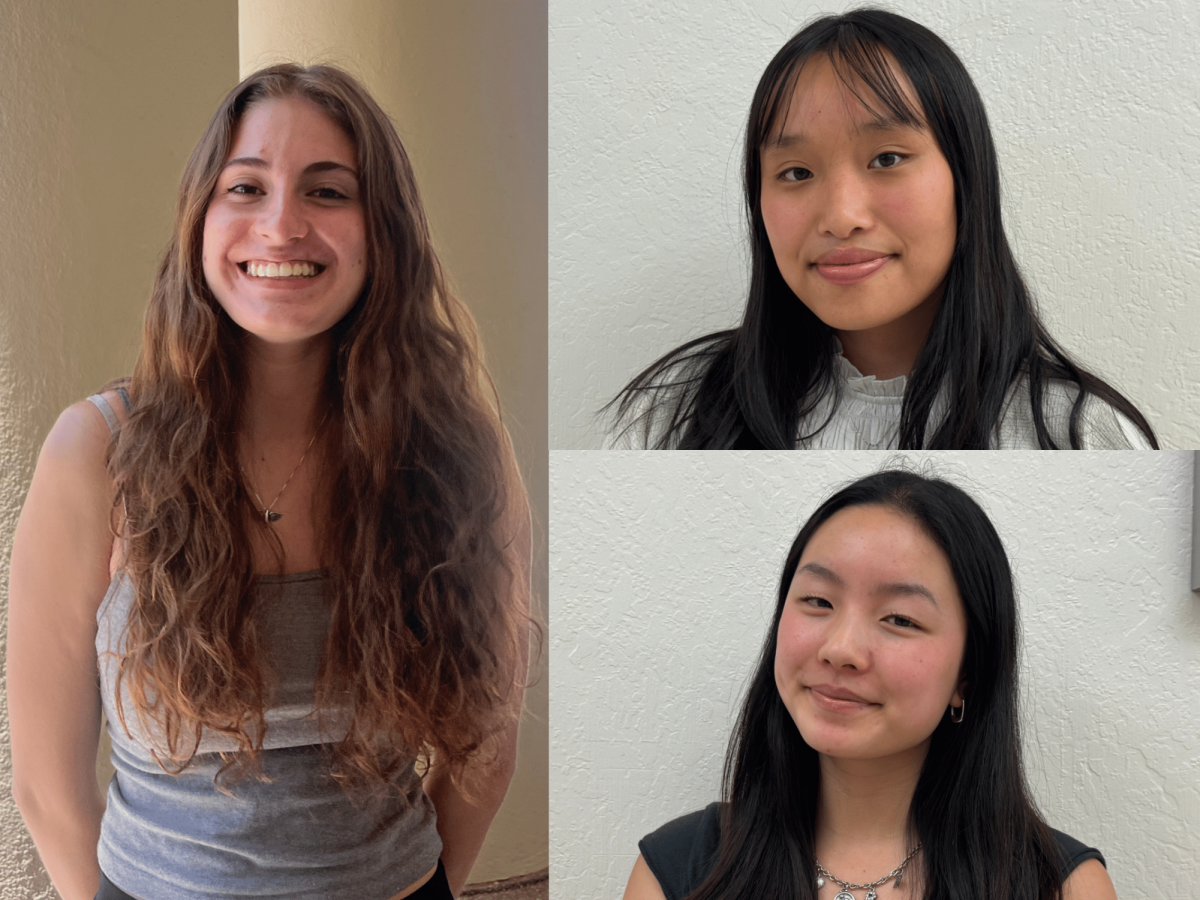

“Today, the Chinese Exclusion Act isn’t in policy, but there’s still this resentment towards Asians…saying we dominate the workplace or educational spaces,” Chinese American junior Eva Chen said.

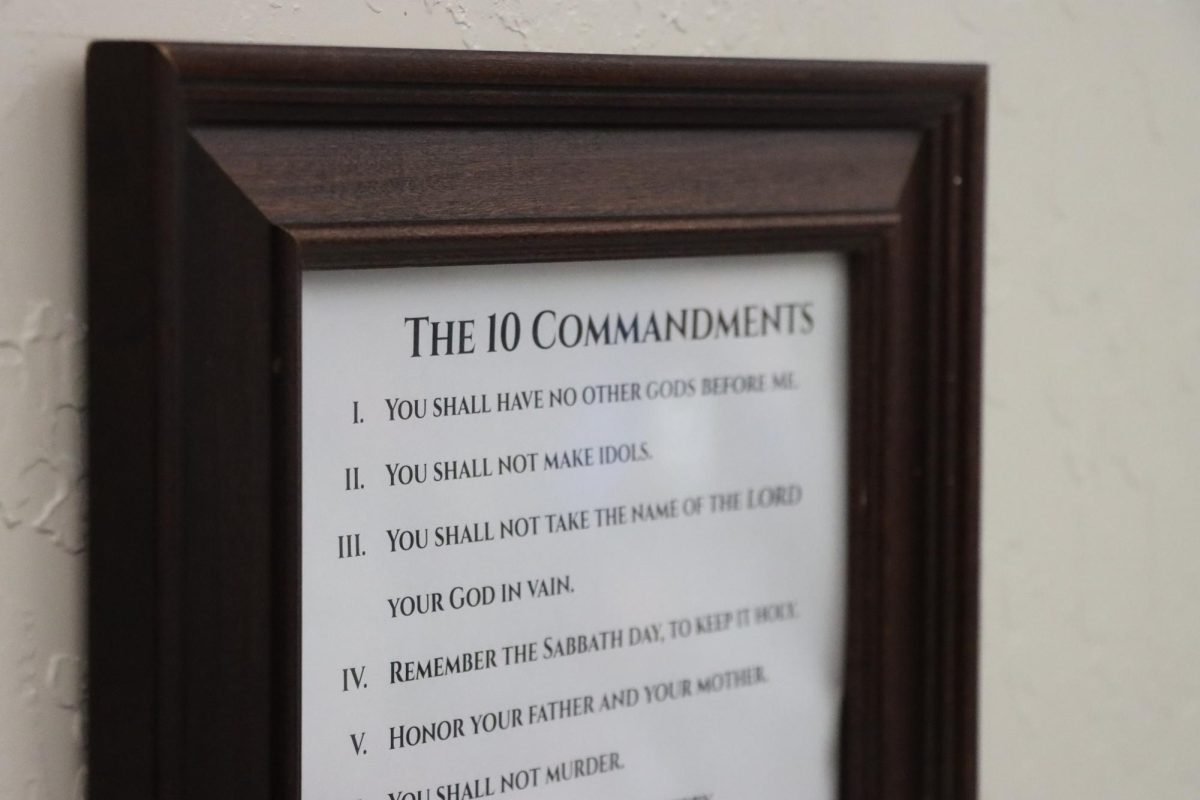

Laws prior to the Exclusion Act such as the Foreign Miners Tax — special taxes targeted at Chinese and Mexican miners in California — and a ban on nonwhites testifying in court made it difficult for Chinese people to deal with discrimination and violence. Even Chinatowns, neighborhoods where Chinese people were forcefully segregated into, were burned down or destroyed. These actions established a sense of “other,” by making assimilation and societal acceptance inaccessible.

“It’s easy to say that the Bay Area isn’t bad, but I think the racism of the Exclusion Act emerges in more subtle ways,” Taiwanese American teacher Jim Chin said. “People say things like, ‘Oh, your English is so good’…it’s not innately malicious, but it’s the kind of thing you say when your gut tells you something about being Asian means you don’t belong or come from America.”

Advanced Placement U.S. History teacher Peter Medine explained that these laws and racist beliefs were a method to enforce anti-Asian behaviors not only institutionally, but also culturally.

“Propaganda from anti-Asian groups accused Chinese people of being opium dealers, and corrupting white women, causing cheap labor and spreading disease — essentially calling them criminals and heathens,” Medine said. “You could compare their efforts to the campaign that the Nazis waged against Jews before they passed all their laws.”

Chinese immigrants also struggled with attacks on Eastern Asian religions, instruments and even hairstyles, as well as stereotypes painting them as robotic, unhuman workers. In the late 1800s, such beliefs landed many Chinese Americans in near-deadly, low paying working conditions. Today, the hard-working Asian stereotype manifests itself differently.

“I have had a few teachers in the past who told me I’m smart, but I doubt they feel that way because it feels like they’re going along with the stereotype, not what I’ve shown them,” Taiwanese American junior Sharon Ku said, explaining that Chinese Americans can be overlooked because of certain assumptions. In a similar note, Chen described how generalizations devalue expression of Chinese cultural values, such as educational excellence or musical ability.

“We forget that the talents we have should be appreciated because it’s been translated into this idea that, of course we’re going to have this,” Chen said, “And in response to that, a lot of Asians…don’t want to be part of this group.”

But in the face of all these repercussions, those apologies do make a difference.

“As people, we’re connected forever to our heritage, our history. So I don’t think that the apologies are overdue,” Chen said, “It’s important that we confront the past to make progress.”

Ku and Chin echoed similarly, but added that the apology needed to be a long term arrangement. Ku described a speech-only apology as “going in a loop.” She added, “We’re not moving forward if we don’t use actions to address our biases.”

Chin agreed, noting that acknowledgment of progression is also important.

“You can be grateful for the opportunities that you currently have while still pointing out that the US has done some pretty awful things in the past,” Chin said. “It’s about finding ways to remind people what history was erased, and then living up to our promise to improve.”