California’s rainstorms don’t solve its droughts. We can fix that.

Photo courtesy of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln

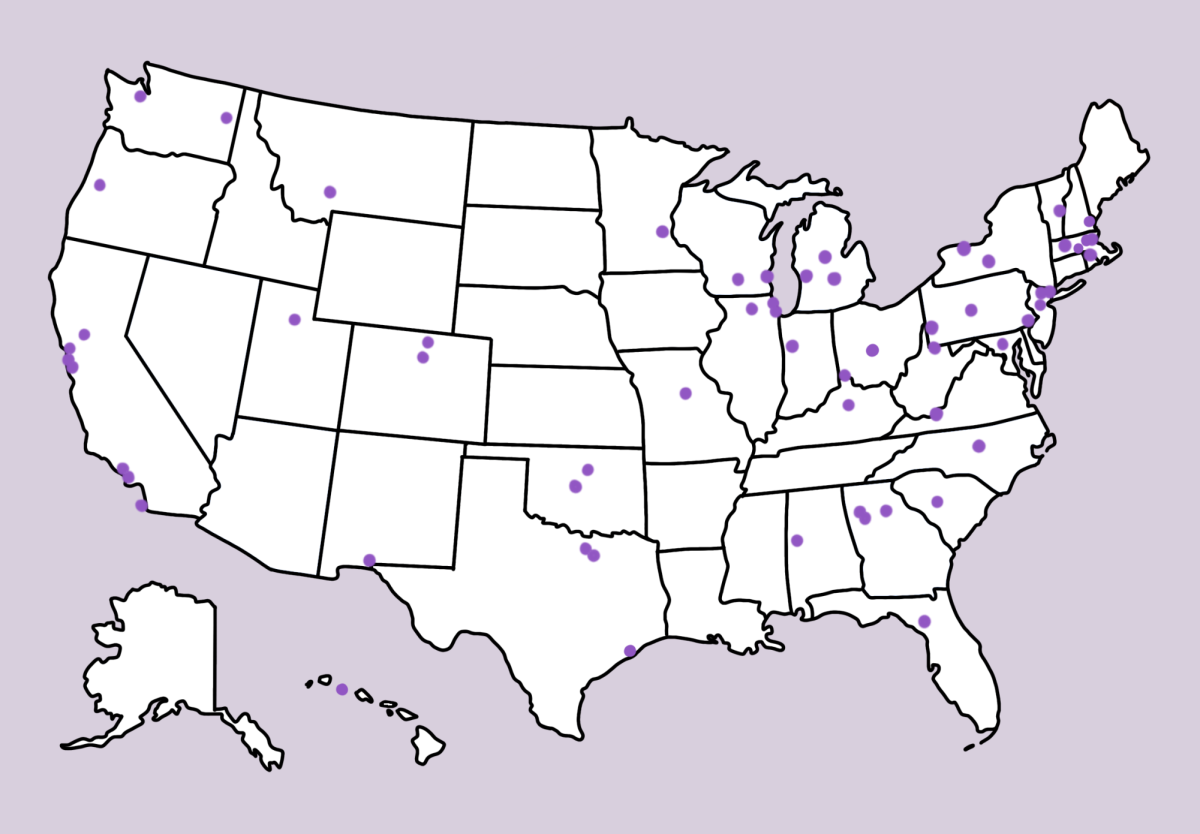

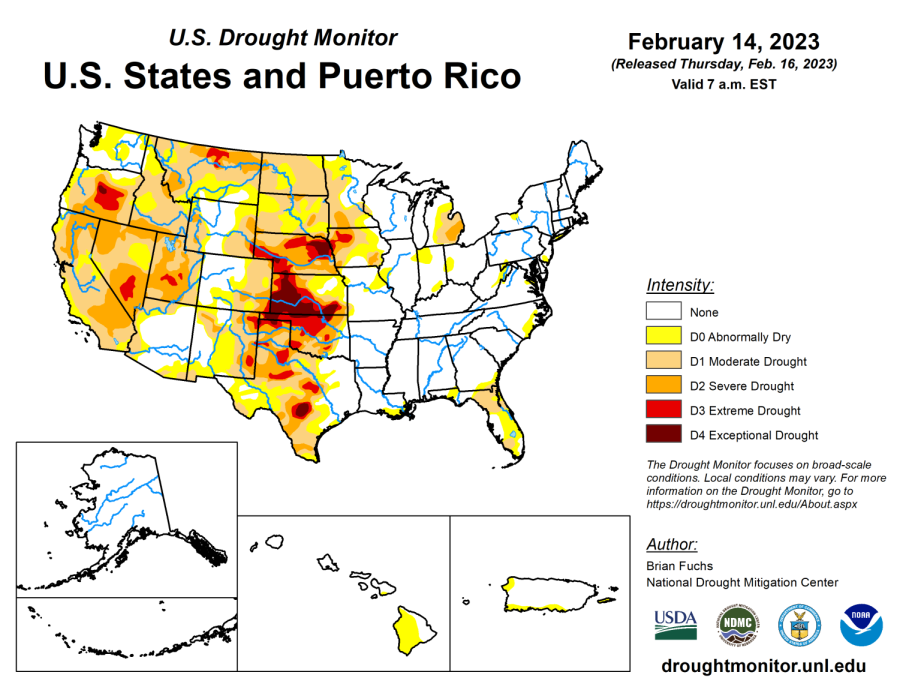

Yet since the storm, California’s surface area that is experiencing drought conditions has decreased from 85% in late 2022 to just under 63% two weeks ago, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

February 17, 2023

Dried up reservoirs, brown hills and dead grass have become the norm in California over the past few decades. But while the state seems perpetually stuck in a drought, every few years, everyone hunkers down and prepares for a mighty rainstorm.

In 2018 and 2019, it was El Niño; this winter, a “bomb cyclone” struck the Bay Area for days on end. But the drought continues. . Is the damage too far gone? Or is there a lack of effort to restore state reservoirs’ water levels to a sustainable level?

It is certain that this year’s cyclone will not resolve California’s ongoing water scarcity on a long-term basis. And although snowstorms in the Sierra Nevada have increased the snowpack and as a result will offer a slightly more long term water supply in the form of snowmelt runoff, a true end to the drought would require years of successive above-average precipitation.

Yet since the storm, California’s surface area that is experiencing drought conditions has decreased from 85% in late 2022 to just under 63% two weeks ago, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. If the state had been properly equipped to take advantage of this “atmospheric river”, that percentage could potentially be even lower.

It’s worth noting that California hasn’t built a new dam since the New Melones Reservoir north of Sonora was constructed in 1980. Meanwhile, the ramifications of climate change continue to grow, sending the state into yearly water shortages with nowhere to store any new supply.

In a 2019 interview with the LA Times, climatologist Bill Patzert estimated that 80% of the region’s rainfall is wasted into the Pacific. This trend exists throughout the state, and could certainly be aided with new construction efforts.

Alarmingly, the Sites Reservoir in the Sacramento Valley has been stagnant in its planning process for some 60 years. The location would in theory store massive amounts of overflow from the Sacramento River during rainstorms — water that otherwise flows straight under the Golden Gate Bridge and into the Pacific.

Gavin Newsom has caught some criticism for these shortcomings in recent years — the issue even came up in his re-election campaign. In an article published by The Federalist, former political opponent Michael Shellenberger faulted Newsom for being pushed around by groups of environmentalists who oppose any and all further development in California.

But this isn’t just a political issue. The west coast is host to many dry climates and large stretches of desert. Naturally, such persistent conditions often lead to long droughts. The issue is amplified, however, by the masses of people who have come to call California their home and rely on its dwindling water supply.

So while mother nature may be at fault for this seemingly ever-lasting drought, populations will continue to grow. For that reason, it is important to find solutions that work around our inconsistent rainfall patterns. Our government needs to wake up from a water-shortage slumber and begin to capitalize on storms that could add supply to important state reservoirs. If we don’t, every rainstorm will look like the record-breaking one in January: damaged housing, power outages, mudslides and a number of fatalities — with no remedy to the drought.