Sleep. It is something that everyone needs, but few high schoolers seem to be able to get, especially at Burlingame.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advises that high school-aged teens get between 8 to 10 hours of sleep every night. Such a sleep schedule is essential not only for feeling recharged during the day but also for performing well in school.

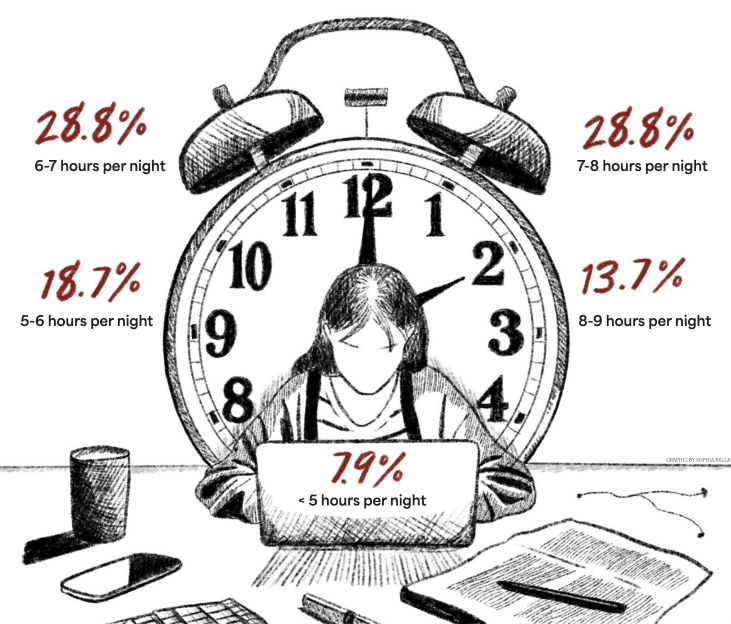

Despite the recommendation, data from a survey completed by 140 Burlingame students found that only 15% get more than eight hours of sleep a night, showing a clear sleep deprivation issue at school.

In the survey, many students attributed their lack of sleep to homework and extracurricular activities.

Senior Janek Pistor is one of these students. Like other seniors, he is applying to colleges while taking multiple Advanced Placement (AP) classes. Pistor noted that his overwhelming schoolwork makes it difficult to get a healthy amount of sleep.

“I think [at Burlingame] there’s definitely a pressure to do well and get into a good college, which means you have to do some good extracurriculars,” Pistor said.

Senior Jack McMahon also feels that the competitive culture at Burlingame plays directly into later sleep times. For him, more work also means less time to hang out with friends and enjoy life outside school.

“[A tough workload] just means that I have to be better about managing my time and cutting down on stuff that’s maybe more fun, like going out on weekends, to make sure I get everything done,” McMahon said.

As school has become more technology-oriented and many assignments are now fully digital, students’ screen times have also increased significantly. For Pistor, this means eight hours a day on his computer working on schoolwork and college applications, which takes a direct toll on his ability to sleep well.

“Since I’m spending so much time on my computer before I go to sleep, I don’t feel as refreshed going to bed,” Pistor said.

Junior Lexie Levitt also noted that since most of her homework is digital, she uses her computer extensively before going to sleep.

“For the first two hours before I go to sleep, I’m probably staring at a computer screen,” Levitt said.

Jeffrey Spoering, an AP Statistics and geometry teacher, recognizes the sleep deprivation problem at school. He believes catching up on sleep after school through naps can help students tackle the issue and feel more energized.

“If you lose some sleep, try to catch up [on] some sleep,” Spoering said. “Not like a two, three-hour nap, like a short half-hour nap,”

While Pistor catches up on sleep during the weekends by letting his body wake up naturally, he believes this method is not a great way to deal with sleep deprivation.

“It’s not healthy to get little sleep and then catch it all up in the weekend,” Pistor said. “That’s not how your body works.”

According to Spoering, the administration has done everything in its power to allow students to get more sleep. And he seems to be right. During the beginning of the 2021-22 school year, the administration moved the start time from 8 a.m. to 8:30 a.m., added flex time twice a week, and changed the 1-7 all-week schedule to block days in order to spread out homework. Therefore, to Spoering, Burlingame’s sleep deprivation issue appears to be more personal.

“I think it’s a family and student-based thing,” Spoering said.

McMahon, however, thinks otherwise. Although he agrees that the issue of sleep deprivation depends on individuals and their responsibilities, he also thinks that the school could cut down on rallies that take up flex time or end school earlier, giving students more time to do schoolwork and allowing them to sleep earlier.

“Most students would use the [extra time] to their advantage and use it to be productive,” McMahon said.

For now, there seems to be no clear solution to the issue. Levitt believes that with America’s current competitive college admissions process, students will continue to get less sleep than they need.

“It’d be nice if we lived in a world where [each class] didn’t require an hour of homework…but I just don’t think that’s where the American educational system is right now,” Levitt said.