As private schools head back to campus, education disparities widen

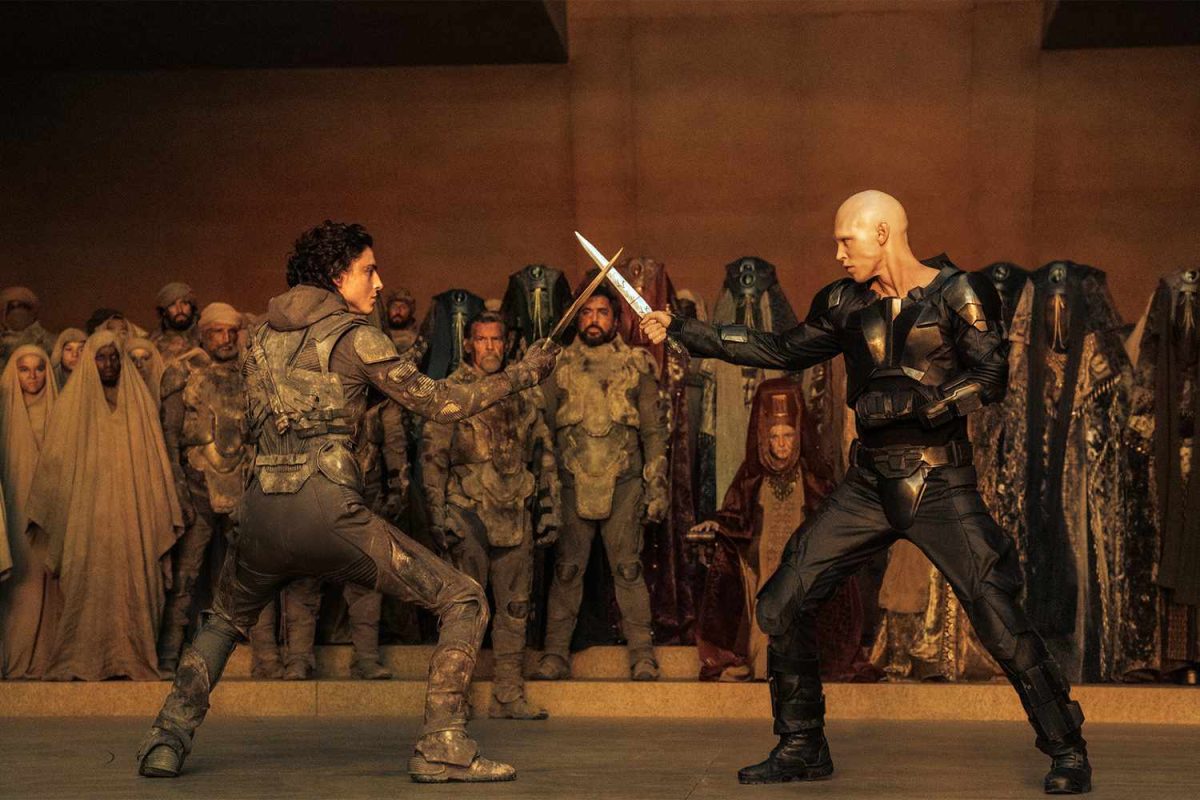

Photo Courtesy of Alison Schieber

An altered high school classroom at Crystal Springs. At the end of October, Crystal Springs returned to a hybrid learning schedule, with students on campus for four days and off for 10.

December 14, 2020

On Tuesday, Oct. 27, 11th and 12th graders at Crystal Springs Uplands School, commonly referred to as Crystal, walked onto campus for the first time in seven months. The same day, San Mateo County dropped into the less restrictive orange tier of Gov. Gavin Newsom’s reopening plan.

Over a month earlier, while Crystal worked on their reopening plan, the San Mateo Union High School District (SMUHSD) Board of Trustees simultaneously ruled that all seven public high schools would remain in distance learning for the rest of the first semester.

For Crystal, the path to reopening was not simple. At the start of summer, administrators planned to begin the school year with hybrid learning, a combination of in-person and distance learning. However, with San Mateo County unable to curb the spread of COVID-19, the school informed students that the first quarter would be entirely remote.

In October, when cases were dwindling and restrictions seemed to be loosening, Crystal jumped at the opportunity to gain approval for in-person learning. Their full-blown reopening plan, perfected and implemented during the long months of stasis, was certified, allowing students to return at the start of the second quarter.

“I really, I really like it,” Alison Schieber, a freshman at Crystal said. “I have like 30 new classmates this year. So I get to meet new people in something that’s not an awkward breakout room,”

With weekly testing, newly installed ventilation systems, altered classrooms that allow for social distancing and expansive tents for outdoor eating and socializing, Crystal seems to have mastered the in-person learning environment. Despite two positive cases, the school plans to continue its hybrid learning schedule into the spring.

Over at Burlingame, as the second semester approaches and cases skyrocket throughout the nation and the county, students’ hope for a return to campus is dwindling.

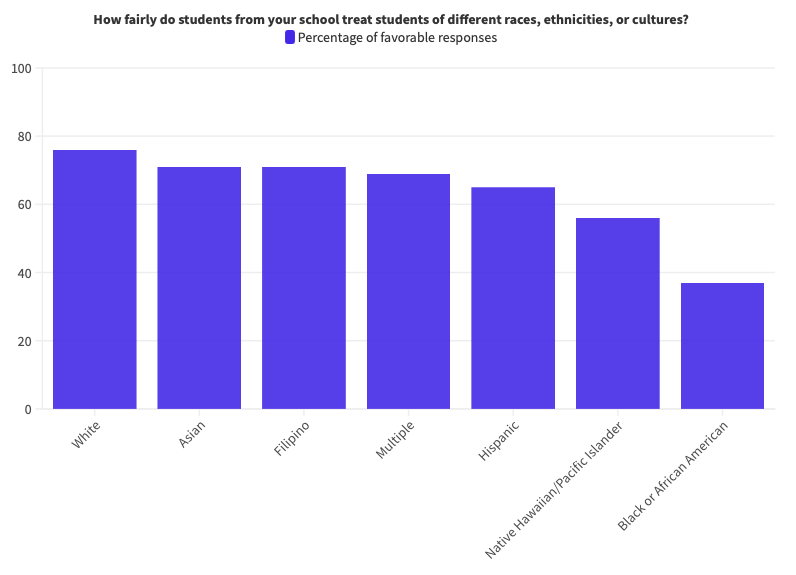

The massive disparities between class and race that COVID-19 exposed are mirrored in the educational system. Across the country, as private schools like Crystal Springs — which has a yearly tuition of over $50,000 — return to in-person or hybrid learning, many public schools like Burlingame remain shuttered, as isolated students log into class from bedrooms.

“What are the elementary schools that have opened?” SMUHSD Superintendent Kevin Skelly said. “They are all in Hillsborough, in Menlo Park, in wealthy communities.”

Class, wealth and resources inevitably influence the quality of education a student receives, but during the pandemic, it has a clear and outsized impact on the learning experience.

When students remain in distance learning, spotty internet, disruptions and limited space create massive learning barriers. And as their districts struggle to create a feasible plan for re-opening, these students that might most benefit from the stability and support of in-person learning are left at home.

At Burlingame, administrators have attempted to provide for under-resourced students by allocating hotspots and bringing learning pods back on campus. However, these assistance mechanisms do not entirely recreate the experience of being at school around classmates and teachers.

There is no question that public schools yearn to return to in-person learning. But strained resources, large class sizes and limited flexibility create immense roadblocks toward reopening.

“We as an association, we as school district administrators, we as teachers, as community members have been demanding funding and support to do this right and do it well,” Craig Childress, the president of the SMUHSD Teachers Association said. “It is a serious problem. And that’s why we’re fighting for the support that we need.”

For the Teachers’ Association, a union composed of over 500 teachers in SMUHSD, the priority before and during the pandemic remains the same: to support teachers in all ways necessary. At this time, that includes advocating, first and foremost, for the health and safety of the community, and secondly, for a conducive learning experience.

“We have to be somewhat of a watchdog,” Childress said. “We have to be somewhat of a protector of teachers’ rights and workers’ rights in terms of safety and working conditions. We’re talking about keeping people safe so that we can do the best at educating students.”

And across the education system, from private to public schools, in urban and rural areas, this will always be the universal goal: to provide students with the best, the safest, the most effective and the most supportive education possible. Unfortunately, this ideal doesn’t often translate to reality.

“We are all working extremely hard,” Childress said. “On many occasions, it’s depressing and demoralizing. People work extremely hard to do what they can, and it’s still not as effective as we would like to be. And that’s extremely frustrating.”

![WASC looks for more than the basic California State standards. According to chairperson Mike Woo, “As new rules and new concerns come up through society, [WASC] look[s] is the school doing something about that. Like the biggest trend post-COVID is mental wellness. So is your school doing something to address the mental health of the students? Along with are they still doing the proper academics?”](https://theburlingameb.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IMG_3401-1200x1200.png)

![“For me personally, I want [others] to see the music program as a strong union because we can really bring out the life of our school,” Vega said. “We need music, you know? Otherwise, things would be really silent and dead.”](https://theburlingameb.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/unnamed-1200x801.jpeg)